Symbolism & Identity: Beyond Practicality

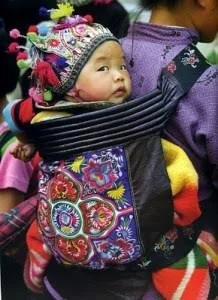

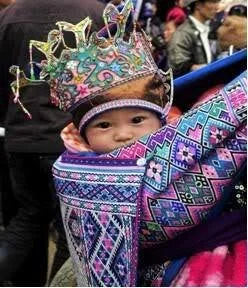

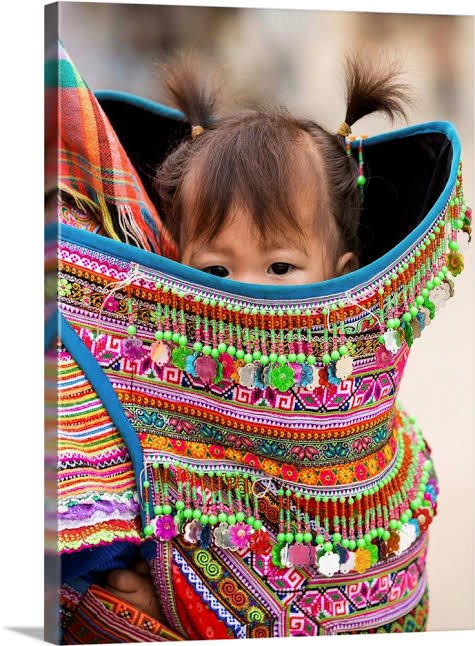

Across the world, baby carriers are far more than practical tools. They are vibrant symbols of identity, belonging, and love — intimate works of art that tell stories with every thread and knot.

In many Indigenous and traditional communities, carriers mark who you are and where you come from. In the Andes, an aguayo’s color palette and weaving patterns can indicate a family’s region, community, or even marital status. The way an aguayo is tied and worn carries additional layers of meaning, reflecting a deep relationship between people, land, and heritage.

In East Africa, khanga cloths are printed with bold, striking messages. These proverbs — sometimes blessings, sometimes advice or social commentary — turn the cloth into a living voice of the community. A mother may choose a khanga with a specific saying to express her hopes for her child or to share her own wisdom publicly.

In Aotearoa, Māori families wrap pēpi in cloaks or woven wraps that speak to whakapapa, the intricate lineage that connects each person to ancestors and land. The act of carrying a baby this way is not just about physical support but about enveloping them in the spiritual warmth of whānau (extended family) and community identity.

In Korea, podaegi often feature carefully chosen embroidery motifs: cranes for longevity, pomegranates for fertility and abundance, peonies for wealth and honor. These designs are believed to offer spiritual protection and blessings, keeping babies safe from harm and bringing good fortune into their lives.

In West Africa, wraps in specific colors or motifs are chosen with intention. Colors can signify spiritual states, stages of life, or protective energies. Certain patterns might invoke ancestral guidance or signal clan affiliations, transforming an ordinary piece of cloth into a powerful talisman.

In Indigenous Australian cultures, particularly among communities in the cooler southern regions, possum skin cloaks carry profound symbolic weight. These cloaks are meticulously crafted from many possum pelts, each piece sewn and incised with designs that record family stories, clan identity, and connection to Country. When babies are wrapped in these cloaks, they are held not only in warmth but in layers of memory and belonging. The cloak becomes a living document of a child’s place within their kinship system and landscape, affirming that they are part of an unbroken line of ancestors and community.

Beyond individual identity, carriers are public statements of cultural pride and collective resilience. Babies carried to markets, festivals, and ceremonies arrive wrapped not just in fabric, but in the story of their people. Through these carriers, the youngest members of the community are introduced to collective rhythms and values, hearing songs, feeling movements, and seeing colors that become part of their earliest memories.

Imagine a global craft display with women proudly displaying their carefully decorated baby carrying devices. Hand-woven, hand-stitched, hand-dyed, hand woven - who would be brave enough to declare any Best In Show? These intricately personalised artworks generally fly under the radar of everyone. Yet they are truly the tapestry of our world.

As modern families work to reclaim and revitalize traditional crafts, baby carriers have become potent symbols of resistance and cultural survival. Weavers reviving ancient dye techniques, artists restoring ancestral patterns, and caregivers choosing to carry in traditional ways all participate in a quiet yet powerful declaration: We remember. We belong. We continue.

Carrying a baby close is a universal act of love — but when done in a cloth imbued with history and hope, it becomes an act of storytelling. It is a promise whispered across generations: you are held, you are known, you are part of us.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.