Cultural Sensitivity and Appropriation in Babywearing

As babywearing continues to grow in popularity worldwide, it is essential to approach it with cultural sensitivity and deep respect. Carrying our babies close may be a universal human instinct, but the ways it is expressed — the designs, materials, and techniques — are deeply specific to each culture and often carry layers of meaning and identity that go far beyond practicality.

We cannot discuss cultural respect without acknowledging the profound and ongoing impacts of colonisation. Across the globe, colonising powers — including English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and others — imposed their own ideals, forcibly erasing or suppressing local ways of life. Beginning as early as the 15th and 16th centuries with European imperial expansion, this process intensified over the centuries and continues to shape the lives of many people today.

In many places, authorities and missionaries discouraged or outright banned traditional child-rearing methods, promoting prams, cribs, and so-called “civilised” parenting ideals modeled after Western norms. In Australia, Aboriginal families were removed from their lands, children were stolen (the Stolen Generations), and cultural practices — including wrapping babies in possum skin cloaks or carrying them in coolamons — were disrupted or lost. In North America, boarding schools and assimilation policies separated Indigenous children from their families and forbade cradleboards and traditional wraps. Across Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, colonisation undermined confidence in traditional methods and replaced them with Western childcare practices presented as “superior.”

It is equally important to remember that colonization did not only happen abroad. Within Britain itself, English colonisation forcibly suppressed the languages, cultures, and traditions of the Welsh, Scottish, and Irish peoples. Beginning in medieval times and intensifying from the 16th century onward, these communities experienced loss of land, language bans, and cultural marginalisation. Traditional child-carrying practices, such as the use of the Welsh nursing shawl (siol fagu), were discouraged or overshadowed by imported English norms.

This internal colonisation also stripped communities of pride and visibility, with long-lasting effects that many are still working to heal today.

In a rural garden setting in the British Isles, a woman carries a young child in a woollen checked blanket, wrapped securely around her body in a hip carry. Her attire — a patterned skirt, cardigan, and slip-on house shoes — reflects mid-20th-century rural clothing, blending practicality with warmth. The use of a household shawl or blanket as a child carrier was a common continuation of longstanding British carrying traditions, where woven cloth served many purposes, including keeping a child close while allowing the caregiver’s hands to remain free..

Recognizing that colonisation came from multiple European powers — not only the English — helps us understand the widespread, layered trauma that has shaped child-rearing traditions and cultural identities worldwide. It also reminds us to avoid oversimplified or inaccurate historical narratives that risk erasing the experiences of colonised peoples within Europe itself.

In this context, the line between appreciation and appropriation becomes even more crucial. Appreciation means learning, acknowledging, and actively supporting the communities who have carried these traditions forward despite centuries of suppression and harm. It means using carriers in a way that honors their origins, sharing their stories, and contributing to their survival and revival.

War in Korea in the early 1950s - bringing western culture thundering into a traditional world

Appropriation, by contrast, involves taking cultural elements — designs, styles, or techniques — without permission, understanding, or acknowledgment, often reducing them to fashion statements or marketing tools. When brands profit from selling “ethnic” or “tribal” inspired carriers without involving or crediting source communities, it repeats patterns of exploitation and silencing.

At the same time, it is important to recognise that the rise of babywearing in Western societies today is not solely about claiming the traditions of others but often about reclaiming lost traditions. Many European and Western cultures once had rich carrying practices that were forcibly suppressed or forgotten through modernization and colonization. As Western families embrace babywearing again, they often do so through the models and techniques that have survived in other cultures — a powerful testament to the resilience and wisdom of these practices. This process of reclaiming can be done in a way that honors and uplifts source communities, rather than erasing or exploiting them.

A Native American woman, dressed in beautifully beaded regalia with fringe and feathered headdress, stands proudly holding a baby in a traditional cradleboard. The cradleboard, decorated with floral beadwork on its tall curved backboard, supports the infant snugly in a swaddled position, offering both safety and comfort. Behind them, the blurred outline of a tipi hints at the community setting. The image reflects the deep cultural significance of cradleboard use, where artistry, practicality, and tradition come together in caring for the youngest members of the family.

Ethical babywearing today means making informed, compassionate choices. It means supporting brands that collaborate with Indigenous artisans and traditional weavers, learning the stories and meanings behind the carriers we use, and uplifting the voices and leadership of people from source cultures in babywearing education spaces.

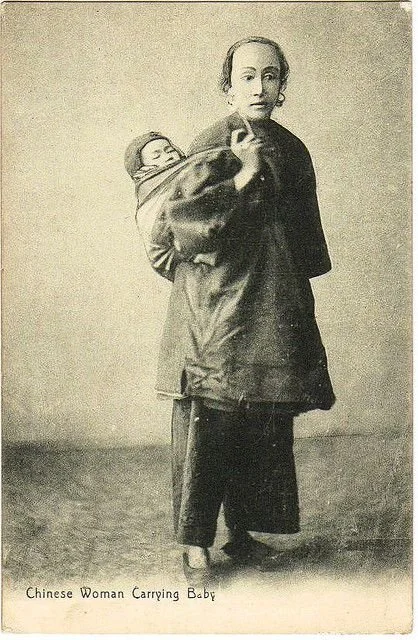

A Chinese mother stands for a studio portrait, her baby carried high on her back in a traditional bei bei style carrier. The fabric is drawn snugly across the child’s body, securing them with their head just above her shoulder so they can see the world around them. She wears a long, loose-fitting tunic over wide trousers, her hair gathered back from her face. The plain backdrop keeps the focus on the mother and child, reflecting the continuity of this centuries-old practice across China’s towns and countryside.

Approaching babywearing with humility and curiosity allows us to nurture our children not just in physical closeness but also in values of respect and justice. When we carry our babies with full awareness of these deeper histories, we transform a personal act into a collective one — a quiet but powerful contribution to healing and cultural survival.

We show our children, from their earliest days, what it means to be in relationship: to each other, to the stories that came before us, and to the world we all share.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.