Māori of Aotearoa: Woven Whakapapa and Community Heart

For the Māori people of Aotearoa (New Zealand), carrying a baby is a deeply spiritual and communal act, embodying the concept of whakapapa — genealogy and connection to all who have come before. Babywearing practices here are woven from flax, family stories, and a profound relationship with land and community.

In this celebrated 19th-century portrait, Māori mother Heeni Hirini (also known as Hēni Te Kirikaramu) is shown carrying her baby on her back in the folds of a beautifully adorned kākahu — a traditional cloak woven with muka (flax fibre), decorated with red and black detailing. Painted by artist Gottfried Lindauer in 1878, this image has become one of the most enduring visual representations of Māori motherhood.

The baby rests snugly against her back, partially wrapped in the body of the cloak, close to her warmth and heartbeat. Rather than a distinct carrier, the kākahu itself is worn in such a way that it becomes a cradle — a practice deeply rooted in Māori tradition. Garments often served multiple functions: to protect, to honour ancestry, and to carry the next generation forward.

Heeni’s moko kauae (chin tattoo) is a visible expression of her identity, whakapapa (genealogy), and mana (prestige). Her adornments, including pounamu earrings, reflect cultural pride and significance, while the child’s peaceful presence offers a powerful glimpse into the relational nature of Māori parenting — grounded in closeness, connection, and care.

Traditionally, Māori caregivers used handwoven flax (harakeke) baskets and wraps to hold babies close during daily activities, whether gardening, gathering food, or participating in communal work. These woven carriers, sometimes called kete or pikau, kept babies warm and secure, allowing them to hear their mother’s heartbeat and the songs of the whānau (extended family).

The process of weaving itself is an act of love and spiritual intention. Weaving harakeke is accompanied by karakia (prayers), embedding protective blessings and the weaver’s hopes for the child into every strand. The patterns often carry deep meanings, representing ancestral lines, natural elements, or spiritual guardians.

Carrying a baby close is also seen as essential for strengthening the bond between child and community. Infants are welcomed into collective life from their earliest days, listening to waiata (songs), learning language, and feeling the rhythms of marae gatherings and daily village life. This closeness fosters a sense of belonging and reinforces the child’s place within the whakapapa and the wider iwi (tribe).

Colonization and Western parenting norms disrupted many traditional practices, introducing prams and distancing approaches to infant care. Yet today, a growing movement among Māori whānau and weavers seeks to reclaim these traditions, weaving them into modern parenting as acts of cultural revitalization and pride.

To be carried in Aotearoa is to be wrapped in more than just flax or cloth — it is to be embraced by ancestors, by earth and sky, and by the living heartbeat of community. It is to grow up knowing that every step forward is supported by countless steps behind you.

c 1940 National Library of New Zealand

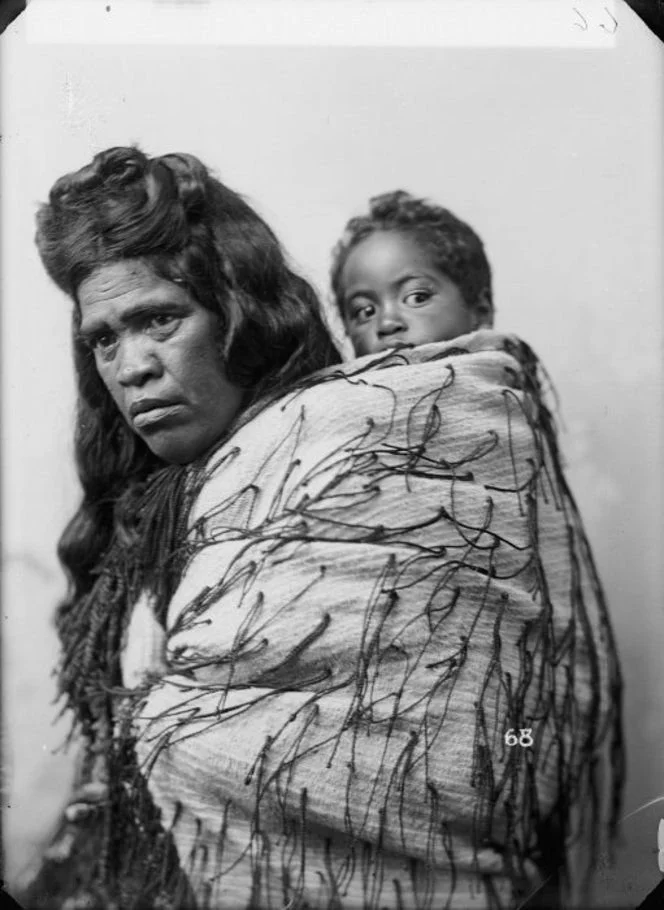

This powerful studio portrait depicts a Māori woman carrying her child on her back, both wrapped together in a beautifully woven korowai (cloak).

The korowai is an iconic garment in Māori culture, carefully hand-woven and often adorned with hukahuka (decorative tassels), as seen here. Such cloaks hold deep cultural significance, representing mana (prestige, authority), whakapapa (genealogy), and the enduring connection to ancestors and land.

In this image, the child is positioned high on the woman’s back, closely nestled and secured within the same cloak. The baby peeks over her shoulder, alert and calm, sharing her warmth and protection. The woman’s serious, steady expression and the elegant way the cloak is arranged speak to the deep responsibility and strength of motherhood, as well as the pride in wearing such an important taonga (treasure).

Carrying a child in a korowai embodies the values of whānau (extended family), aroha (love), and kaitiakitanga (guardianship). The closeness facilitates constant connection and reinforces the deep bonds between caregiver and child, crucial to Māori ways of being and raising tamariki (children).

This image is more than a record of babywearing — it is a portrait of cultural resilience, intergenerational care, and the profound beauty of Māori maternal traditions.

This beautiful vintage photograph depicts a Māori mother carrying her baby on her back, both warmly wrapped in a checked wool blanket.

The baby is positioned high, looking out over the mother’s shoulder, snugly enclosed by the blanket. The mother’s relaxed, smiling expression shows confidence and ease, suggesting that carrying her child in this way was both natural and deeply familiar. The baby wears a knitted cap, adding further warmth and protection.

Blankets like this were commonly adapted into improvised carriers by Māori and many other Indigenous communities during the colonial period, as woven cloaks (korowai) gradually became reserved for special occasions or formal wear. Families continued to prioritise closeness and warmth, using available materials in practical ways that preserved connection and mobility.

Carrying in this style keeps the baby secure, maintains body warmth, and allows the mother to move freely, while keeping her child close enough to feel her breath and heartbeat.

This image beautifully illustrates the enduring value of keeping babies close — a core part of Māori parenting traditions — and highlights the adaptability of Indigenous mothers in merging traditional practices with introduced materials.

In this powerful portrait, a Māori woman carries her baby on her back, wrapped securely in a finely woven traditional cloak adorned with decorative tassels and tufts. The mother wears a moko kauae (chin tattoo), symbolising her whakapapa (genealogy), identity, and mana wāhine (the prestige and authority of women).

The baby peeks over her shoulder, held close in the embrace of the cloak, a method that keeps pēpi safe, warm, and connected to the mother’s body and heartbeat.

This image beautifully captures the strength and dignity of Māori women, the importance of whakapapa, and the intimate, nurturing bond between mother and child. It is a moving reminder of the resilience and continuity of Māori cultural practices of babywearing — practices that centre love, closeness, and the collective care of tamariki (children).

In this evocative historic photograph, two young Māori girls stand together in a rural village setting in Aotearoa (New Zealand). The older girl on the right carries a baby sibling wrapped close against her body in a checked wool blanket — a practical, protective way to keep little ones warm and secure.

The blanket is folded and tied in a way that echoes traditional Māori practices of using cloaks (kākahu) and woven wraps to hold babies on the back or hip. Even as wool blankets replaced earlier woven flax garments (pākē), the fundamental practice of babywearing remained — keeping infants close while freeing the caregiver’s hands to help with daily life.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.