Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Country, Kin, and Cloaks

⚠️ Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that the following content contains images of people who have passed away.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, carrying a baby is a profound expression of connection to Country, kinship, and culture. These practices reflect tens of thousands of years of continuous care and an unbroken relationship with land and sea.

Among many Aboriginal groups, infants were carried using possum skin cloaks or nestled in coolamons — shallow wooden carriers shaped to cradle a baby safely. Possum skin cloaks, meticulously crafted and decorated with clan markings and Dreaming stories, held infants close while protecting them from the elements. When wrapped around a baby, these cloaks embodied warmth, protection, and spiritual connection to ancestors and Country.

Coolamons, carried on the head or under the arm, allowed caregivers to move across Country with babies secure and close. Babies remained part of daily rhythms — hearing language, songlines, and stories shared by elders.

For Torres Strait Islander families, woven baskets and cloth wraps were used to carry babies across both land and sea. Babies were kept close as families fished, gardened, and traveled between islands, ensuring children learned to feel at home with the tides and village life from birth.

Though colonization disrupted these practices, many families today are reclaiming and revitalizing them as acts of cultural renewal and healing.

To be carried in these traditions is to be embraced by Country, kin, and story — wrapped in layers of care that affirm: “You belong here. You are loved. You are part of us.”

A family’s six-generation tradition with the coolamon

In Central Australia, the age-old Aboriginal tradition of using a coolamon to cradle and nurse babies continues strongly in the family of Amanda Kantawara, a proud Western Arrernte and Luritja woman from Hermannsburg (Ntaria).

Amanda has used the same coolamon — lovingly carved from the bean tree (Erythrina vespertilio, known in Arrernte as atywerety) by her great-grandmother in 1983 — to care for each of her children, including her newest baby, Senna Malbunka.

Passed down through six generations, this 41-year-old vessel has cradled not only Amanda’s babies but those of her siblings, their children, and now their grandchildren.

Amanda shares that the coolamon supports her babies' bodies, making feeding and moving them easier, while helping them sleep soundly and stay safely positioned.

“It’s so much easier to move her around and breastfeed when she is lying in the coolamon,” she explains. “It gives her a good night’s sleep and helps keep her spine and hips straight.”

She also places Senna in the coolamon while she sleeps in a bassinet or cot, and even when tidying the house nearby.

While this tradition has sadly faded in many places, Amanda’s story shows the enduring strength of cultural practices and the deep connection between family, country, and kin.

“This is the first coolamon I have seen being used for multi-generations of midwifery care in Central Australia,” says NT Health midwife Glenda Gleeson. “It is a beautiful example of keeping cultural practices alive and strong.”

This remarkable photograph depicts Teenminnie, a Ngarrindjeri woman from the Adelaide region in South Australia, captured around the 1870s. She is shown wearing a large possum skin cloak, expertly wrapped to carry her toddler securely on her back.

Possum skin cloaks are deeply significant cultural items for many First Nations peoples in southeastern Australia. They provide warmth and protection but also carry stories — each cloak carefully stitched and often incised or painted with designs representing family, Country, and identity.

Teenminnie stands firmly on the land, her gaze strong and composed, embodying resilience and deep connection to her child and community. The photograph, taken by Samuel White Sweet (1825–1886) and held in the State Library of Victoria collection, offers a rare and intimate glimpse into traditional child-carrying practices and everyday life at the time.

This remarkable studio portrait depicts an Aboriginal mother carrying her child on her back in Adelaide, South Australia, between 1874 and 1879.

The mother uses a large cloak, clearly visible here as kangaroo pelt, to wrap and support her child. The baby sits high on her back, looking outward over her shoulder, securely nestled against her. The cloak is carefully arranged to create a deep pocket or pouch, keeping the child close and protected. Over her shoulders, she has an additional cloth layer — a striped shawl or blanket — providing further warmth and support.

Kangaroo and possum skin cloaks were highly valued by Aboriginal people in southern Australia. These garments were practical and deeply cultural, serving as protection from the elements and as a way to carry babies safely and comfortably. Each cloak carried personal and family stories, and children often grew up wrapped in the same cloak that kept their mother warm.

This image powerfully captures the adaptability and strength of Aboriginal mothers, showing how caregiving was integrated into daily life. The combination of traditional materials with introduced fabrics highlights the resilience of Aboriginal families navigating a changing colonial world, while maintaining strong bonds and cultural practices.

This striking historical portrait depicts an Aboriginal Australian woman carrying her child wrapped in a traditional possum skin cloak.

Possum skin cloaks were carefully crafted from multiple sewn-together pelts, often decorated with incised patterns that told stories of family, Country, and identity. In southeastern Australia, these cloaks were essential for warmth and protection against the elements and were worn throughout life — from infancy through adulthood.

Here, the mother carries her child on her back, securely enclosed within the cloak. The child’s head peeks over her shoulder, close enough to feel her warmth and hear her voice. The cloak envelopes them both, allowing the mother to move freely across the land while keeping her baby safe and connected.

The possum skin cloak is more than a garment — it embodies cultural identity, deep family bonds, and the profound knowledge systems of First Nations peoples, showcasing their resourcefulness and care for the next generation.

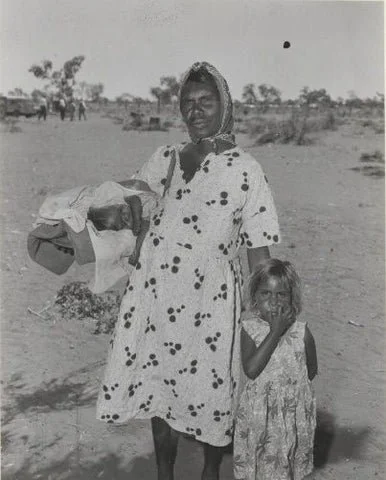

This striking photograph depicts an Aboriginal mother standing in a sandy, open landscape, holding her infant in a makeshift carrier while her older child stands close by.

Here, the mother carries her baby in what appears to be a cloth sling or wrap, fashioned from a piece of fabric tied over her shoulder and supporting the baby across her front. The baby lies in a reclined or cradle position, partially covered from the sun and elements. This simple cloth method reflects a practical, adaptable approach to carrying, using readily available materials to keep the baby close and secure.

Her dress and headscarf suggest a period when mission or settlement life had influenced clothing styles, yet the practice of keeping babies on the body remained strong. The older child stays close, showing the interconnectedness of siblings and the central role of children in family and community life.

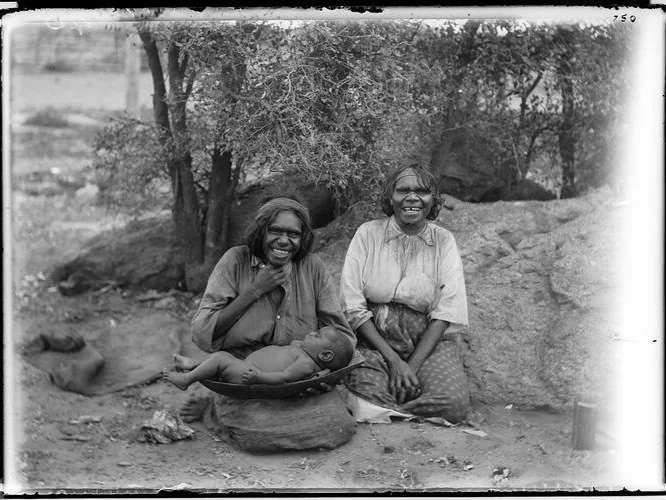

This wonderful historical photograph depicts two Aboriginal women sitting on the ground, sharing a moment of joy and connection.

In the foreground, one woman holds a baby resting in a coolamon — a traditional, shallow wooden carrying vessel. The baby lies comfortably inside, supported on the woman’s lap, creating a secure and soothing space. Coolamons were highly versatile: used to carry babies, gather food, collect water, and cradle children while resting or travelling.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.