Middle East & North Africa: Stories in the Desert and Oasis

Across the vast stretches of desert, lush oases, and ancient cities of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), carrying traditions are deeply intertwined with survival, modesty, and community connection. While less widely documented than in some other regions, these practices reveal a quiet resilience and adaptability shaped by nomadic life, harsh climates, and rich textile traditions.

In nomadic Bedouin communities, mothers often used long rectangular cloths or shawls to secure their babies while traveling across the desert. These cloths, sometimes adapted from everyday garments like the abaya or hizam, allowed mothers to keep their babies close and protected from sun, sand, and wind. Babies nestled against the chest or back would hear the steady heartbeat of their caregiver, finding comfort in the rhythm of movement across vast landscapes.

In the Levant — encompassing present-day Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan — rural women traditionally used long wraps or cloths to carry babies while tending fields or moving through markets. These wraps often doubled as modesty garments or sun protection, seamlessly integrating the baby into the flow of daily work and social life. Historical photos and oral histories reveal glimpses of mothers working the land with babies tied securely, forming an unbroken bond of closeness and care.

Among Kurdish communities spread across Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, babywearing traditions reflect a deep connection to land, family, and resilience. Kurdish women have long used long woven sashes or cloth wraps — often richly patterned with regional motifs — to carry babies on their backs or hips. These wraps allow mothers to keep their little ones close while working in fields, navigating mountain paths, or moving through bustling village life. Each cloth carries stories of clan identity and protective blessings, passed down through generations by demonstration and song. To be carried in Kurdish tradition is to feel the warmth of kinship and the echo of mountain winds, wrapped securely in both fabric and love.

Among the Yörük people of Anatolia — a historically nomadic Turkic community — the kolan stands as a powerful symbol of resourcefulness and connection. This long, narrow woven band, originally used to secure tents or carry loads, was ingeniously repurposed for babywearing. Wrapped around the shoulders and back, and often supplemented with a cloth or blanket, the kolan allowed caregivers — even older siblings — to carry infants securely while moving through mountainous landscapes and tending to daily life. Though not always ergonomically comfortable by modern standards, the kolan reflects a deep commitment to keeping babies close and included in every moment of community life. In each woven thread, we find stories of family, resilience, and the gentle ingenuity that has carried generations forward.

In North Africa, particularly among Amazigh (Berber) communities, babywearing practices reflect deep ties to textile artistry and clan identity. Women wove thick, colorful blankets and shawls used both as clothing and as carriers, their geometric patterns symbolizing family lineage and protection. These carriers not only served practical needs but also expressed pride and cultural continuity in a region marked by centuries of cultural exchange and adaptation.

Colonization, urbanization, and shifts in modesty norms have all contributed to a decline in traditional babywearing in MENA regions. Prams and strollers, often introduced as symbols of modernity and status, replaced wraps and cloths in urban centers. Despite this, many rural and nomadic families have quietly preserved these practices, carrying forward ancestral knowledge through daily life and storytelling.

Today, as conversations about cultural revival and ancestral practices gain momentum, there is renewed interest in reclaiming and honoring these traditional ways. In weaving cooperatives, markets, and family gatherings, the echoes of these ancient carrying practices continue — a testament to the enduring strength and adaptability of MENA mothers and communities.

To carry a baby in these lands is to weave a thread between desert winds and oasis palms, between ancestor and future, holding the child close to the heart of the family and the soul of the land.

In North Africa, babywearing traditions are woven into the long history of desert life, market streets, and village gatherings. From Morocco to Egypt, mothers have used long shawls and cloth wraps to carry their babies close, often on the hip or back. These cloths, sometimes simple cotton or beautifully handwoven wool, may feature soft stripes or geometric motifs that echo the region’s artistic heritage. Among rural Egyptian women, a melaya or fouta is often wrapped around both mother and child, allowing her to keep moving freely through daily tasks. In Tuareg and Amazigh communities, the cloth might be dyed a deep indigo, connecting the baby to protective and cultural symbolism. Although modern life has shifted some of these practices, each wrap still tells a story of family, resourcefulness, and the timeless comfort of carrying a child heart to heart.

Among the Bedouin, babywearing is a seamless part of life in the shifting sands and star-filled nights of the desert. Mothers use long rectangular cloths — often the very same shawls they wear as head coverings — to secure their babies against their backs or hips. These cloths, made of breathable cotton or fine woven wool, are chosen carefully to protect against the scorching heat by day and the cold by night. While typically simple in decoration, they embody the Bedouin spirit of adaptability and grace. A mother can unwrap, adjust, and retie her cloth as needed, all while tending goats, preparing tea, or gathering firewood. In this tradition, carrying is more than a practical solution; it is an intimate dance of warmth, rhythm, and connection, passed quietly from mother to mother across generations beneath the desert moon.

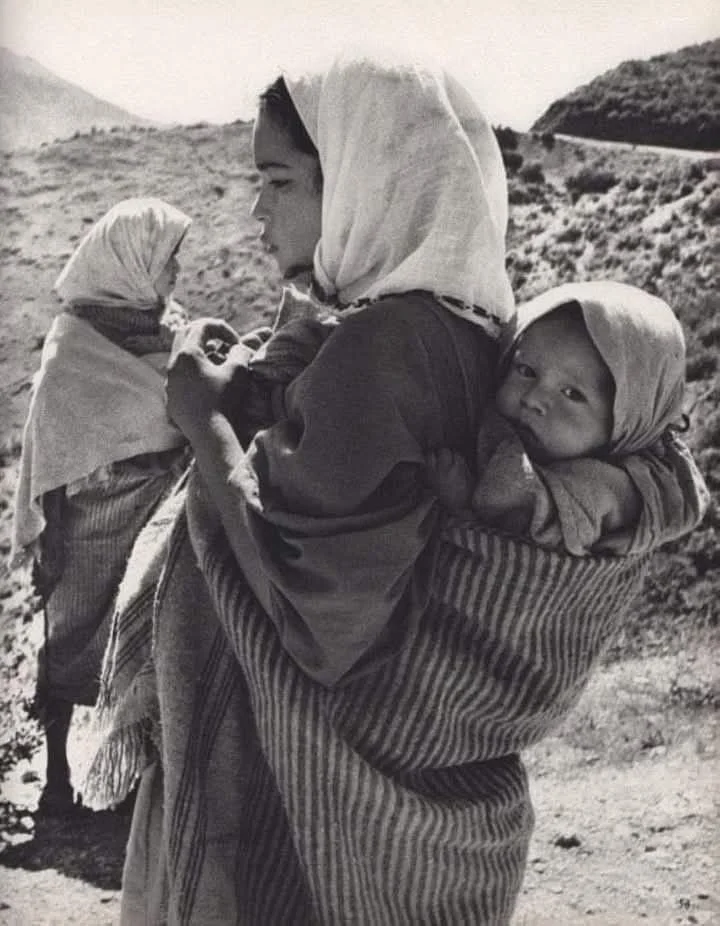

This striking black-and-white photograph shows a young girl carrying her sibling on her back using a simple cloth wrap, somewhere in the Middle East or North Africa. Both children wear head coverings, which can be seen in various rural and traditional communities across this broad region. The wrap is tied firmly around the older child’s waist and shoulders, keeping the younger child securely against her back. This method of carrying, sometimes called a torso carry or blanket carry, is a practical solution that has been used for centuries to allow older siblings (and mothers) to help care for little ones while remaining active. It highlights the strong familial bonds and shared caregiving practices that are common in many traditional societies.

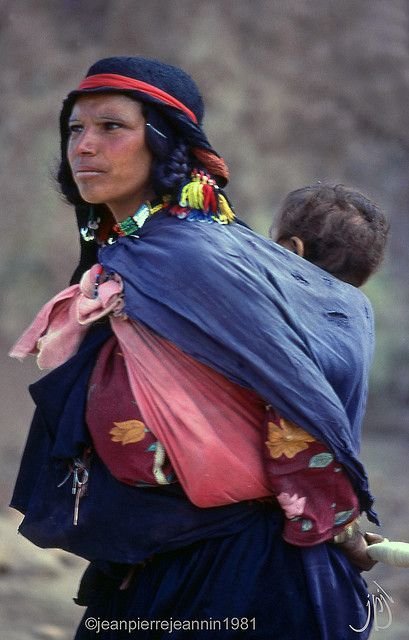

In the rugged landscapes of Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, Amazigh (Berber) mothers carry their children on their backs using richly patterned shawls or handwoven cloths, often tied securely across the chest. This practice allows them to navigate rocky paths, tend flocks, and work the land while keeping their children safe and close. The textiles, adorned with geometric motifs and bright colors, reflect centuries of cultural heritage and deep connections to land and family. Babies carried this way share the warmth of their mother’s body, the scent of earth and herbs, and the rhythmic sway of daily life. To be carried in an Amazigh shawl is to grow up wrapped in stories, resilience, and the enduring strength of mountain traditions.

This beautiful image shows an Ethiopian mother carrying her baby on her back using a shamma, a traditional handwoven cotton wrap. The baby sits snug and secure, warmly wrapped and sharing in the day’s experiences with wide-eyed curiosity. The mother’s elegant head covering and the shamma’s fine, white weave with decorative edges speak to Ethiopian textile artistry and cultural pride. In Ethiopia, the shamma serves not only as clothing but as a practical and deeply symbolic means of nurturing and protecting little ones. This tender moment reminds us that babywearing is far more than a practical tool — it is a living expression of love, heritage, and connection that travels through generations.

This mother, likely from the Qashqai nomadic people of Iran, carries her child on her back using a long cloth tied around her shoulders and waist. Among many nomadic and rural communities in Iran, especially the Qashqai and Bakhtiari, babywearing is practical and essential for moving through mountainous terrain while tending to flocks and daily tasks. The child is secured snugly but simply, in a style similar to a traditional wrap or shawl, allowing close contact and flexibility. The mother’s layered and patterned clothing, along with the pastoral setting, reflects the rich cultural identity and strong connection to land and movement typical of Iran’s nomadic groups.

This vibrant image captures a mother from a rural pastoral community in Anatolia or the Middle East, carrying her child on her back while tending a herd of goats. Wrapped simply but securely, the baby sits high and close, curiously watching the world over her mother’s shoulder. Her bright headscarf and lively green top reflect the rich colors and practical styles of the region. This beautiful scene illustrates how babywearing supports the blending of nurturing and work, allowing mothers to stay connected to their children while fully engaged in daily pastoral life — a timeless expression of love and resilience."

In rural villages of North Africa, mothers carry their children wrapped in simple checked cloths, moving through stone courtyards and sunlit fields with quiet strength. Here, a mother stands wrapped in deep crimson, her child nestled safely against her back beneath the familiar folds of a red-and-white scarf. Each step echoes the rhythm of ancestral stories and the warmth of communal life, where children grow up held close to the heart of daily work and village laughter. In this tender embrace, the child learns the scent of earth and the gentle sway of a mother’s love — woven together in the humble beauty of cloth and care.

In the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco, Berber mothers carry their children wrapped in bright, layered shawls that echo the vivid colors of mountain wildflowers. Here, a mother strides forward, her baby nestled securely against her back beneath carefully tied cloth. Each tassel and embroidered detail carries family heritage and the spirit of resilience shaped by mountain winds and sun. As mothers move through fields, markets, and rugged trails, their children learn to see the world from a place of warmth and safety — woven into the fabric of daily life, carried with strength and ancestral pride.

Among the Berber (Amazigh) women of Morocco, carrying a child in a simple cloth tied securely across the back is both a practical necessity and a quiet expression of deep connection. In rugged mountain landscapes and rural valleys, mothers wrap their babies snugly against them, allowing for hands-free work and easy movement through rocky terrain. This method embodies resilience and adaptability — the child nestled close to feel the mother’s warmth and rhythm, while she continues her daily tasks. The vibrant textiles and layered headscarves speak to cultural pride and identity woven into everyday life.

In eastern and southeastern Turkey, particularly among Kurdish and Anatolian village communities, babywearing is deeply rooted in daily life. Using long, multipurpose cloths tied securely around the body, mothers carry their children while continuing farm work, household tasks, or community gatherings. This image beautifully illustrates the practical strength and tender devotion of these women — a quiet testament to the seamless way care is woven into every part of life.

This powerful historical photograph shows a mother from North Africa — likely Morocco or a neighboring Maghreb region — carrying her baby securely on her back in a large, striped woven cloth. The baby rides upright and close, calmly observing the world from the safety of their mother’s back. Her headscarf and practical wrap reflect the region’s traditions of modesty, sun protection, and deep cultural heritage. In the background, another woman carries her child in the same loving way, emphasizing the shared wisdom and community strength in these practices. This image beautifully illustrates how babywearing has always allowed mothers to move freely through their landscapes while keeping their little ones nurtured and connected."

This evocative historical photograph likely depicts women from the Middle East or North Africa, perhaps Palestinian or Bedouin communities, caring for their children in everyday life. One mother carries her child asleep on her back in a simple cloth wrap, tied over one shoulder in a traditional and practical style that allows her to continue her work or walking hands-free. The other woman cradles her child in her arms, both of them sharing a quiet, tender moment. Their modest, patterned clothing and head coverings reflect the cultural and practical dress of the region. This image beautifully illustrates how babywearing and carrying in arms were woven into daily rhythms — each style chosen for comfort, practicality, and deep connection.

Morocco

This Berber (Amazigh) mother from the Atlas Mountains of Morocco carries her child close, wrapped securely in a simple cloth that echoes centuries of mountain tradition. Among Berber communities, carrying a baby this way allows mothers to navigate steep, rocky paths and tend flocks while keeping little ones warm and safe. The textiles — often woven with bold geometric patterns — are deeply tied to identity and resilience, embodying both practicality and quiet strength. To be carried here is to learn the sharp wind of the high passes, the scent of herbs and stone, and to feel deeply rooted in a lineage of endurance and care.

This mother from Morocco carries her child high on her back as she navigates her daily work, here gathering and transporting fodder. In rural Berber (Amazigh) communities, simple cloth wraps and shawls are skillfully tied to keep babies secure while allowing mothers to work hands-free in mountainous and arid landscapes. The wraps, often repurposed from everyday textiles, are practical and deeply embedded in the rhythms of life. Carried close, the baby shares in the scent of earth and harvest, the warmth of a mother’s back, and the gentle sway of each step — learning from the land and family long before taking their own.

In this striking scene, we see a mother walking down a sunlit road with her child snugly carried on her back in a wide, woven cloth. The bright stripes of the carrier echo the colors of traditional Anatolian textiles, reflecting both practicality and cultural artistry. This style of babywearing, found in various rural parts of Turkey and neighboring regions, allows mothers to keep their little ones close while tending to daily tasks or traveling long distances on foot. It beautifully symbolizes the strength and resilience of women who carry both the physical and emotional weight of their families — and do so with grace and warmth.

In this vibrant 2003 photograph taken in Tinerhir, Morocco, a Berber (Amazigh) mother beams joyfully as she carries her baby warmly wrapped on her back. Her bright green headscarf, adorned with small decorative elements, frames her smiling face and highlights the gentle tattoos on her chin — traditional markings that reflect identity and beauty in some Amazigh communities.

The baby, dressed in a cozy blue hood and bundled snugly in a thick pink blanket, gazes out with sparkling eyes and a soft, curious smile. The wrapping style keeps the child close and secure, sharing warmth and allowing the mother to move freely through the rugged mountain landscape.

Pascal Mannaerts

In this beautifully hand-colored historical postcard titled "Bédouine portant son enfant" (Bedouin woman carrying her child), a Bedouin mother stands barefoot, carrying her young child securely on her back. The child, bright-eyed and smiling, peeks over her shoulder, wrapped warmly in patterned cloth and tied close to her body.

The mother’s garments — a deep indigo or blue robe and light inner layers — are loose and practical, allowing freedom of movement in desert or village life. Her head is wrapped with colorful scarves, echoing the layered and multifunctional textile traditions of Bedouin women, who often used scarves both as adornment and for sun protection.

The carrying style, using a large piece of cloth wrapped around the shoulders and chest, allows for secure back carrying, keeping the child safe and close while enabling the mother to walk long distances or perform daily tasks.

As with many studio postcards from this era, especially those made for European audiences, it’s important to recognize that these images were often posed and sometimes idealized, and may not fully represent daily realities or regional diversity among Bedouin groups.

Despite this, the image radiates warmth and connection — a universal testament to the strength and care of mothers everywhere, and to the timeless art of keeping little ones close through simple, ingenious cloth carries.

In this striking historical studio photograph, two Egyptian Fellahin women (agricultural workers) are pictured with their children. The standing mother carries her child high on her back using a large striped cloth wrap, the baby perched confidently and looking out with bright curiosity. The mother’s face is partially covered by a veil, and her layered garments reflect the traditional rural dress of Egyptian peasant women of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Beside her, another woman sits on the ground, her face also veiled, and her child who rests contentedly in her lap. Her white outer wrap drapes around them both.

The large striped cloth used for carrying — often a multi-purpose garment or shawl — allowed Fellahin women to keep their babies close while working in the fields or tending to daily chores, embodying a deeply rooted tradition of practical, intimate caregiving.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.