Africa: Carried in Bold Cloth and Song

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the art of carrying a baby is not merely a caregiving technique — it is an expression of community, connection, and continuity. In many African cultures, the community raises the child; the phrase "it takes a village" is not just a saying but a lived reality. The baby on a caregiver’s back is part of every rhythm: market days, farming, dances, family gatherings, and storytelling circles around the fire.

Throughout West, East, and Southern Africa, brightly colored cloth wraps — kangas, khangas, and capulanas — are used to secure babies snugly to the back. These textiles are more than just fabric; they speak. Messages woven or printed into the cloth might convey blessings for the child, proverbs about life’s challenges, or statements of identity and resistance. Each pattern and color choice can carry meaning specific to the family, region, or moment in time.

In this image, a mother carries her baby on her back using a brightly patterned cloth wrap, a common and beloved style throughout West, East, and Central Africa. The baby sits snug and high, able to rest or look around while feeling the warmth and rhythm of the mother’s movements. The cloth — often called a kanga, lappa, or pagne, depending on the region — is wrapped securely around both mother and child and tied at the front or tucked without knots, demonstrating incredible skill and cultural tradition. This method reflects a deeply practical and intimate approach to caregiving, allowing mothers to work in the fields, cook, fetch water, or visit markets while keeping their babies close and fully included in daily life.

Carrying styles in Sub-Saharan Africa typically involve simple but highly effective knotting methods, with the baby seated wide-legged against the caregiver’s back, supporting healthy hip development and spine alignment. The caregiver’s movement naturally soothes the baby, mirroring the gentle sway experienced in the womb. Meanwhile, the baby remains an active participant in the world, learning social cues, language, and community rhythms from their secure vantage point.

Spiritually and emotionally, babywearing affirms a deep sense of belonging. Elders often teach new mothers how to tie cloths securely, passing on not only practical skills but also songs, blessings, and stories. This practice binds generations together, ensuring that each baby grows up literally and symbolically “wrapped” in their family’s love and cultural knowledge.

Modern challenges — including urbanization, the rise of prams and strollers, and Western parenting ideals introduced through colonization — have threatened to shift these traditions. Yet in many regions, babywearing remains strong, proudly carried forward as a symbol of cultural resilience and identity. Younger parents and urban mothers are now blending tradition with modern life, proudly tying babies onto their backs while moving through busy city streets.

Through the vivid cloth, the gentle sway, and the warm touch, Sub-Saharan African babywearing reminds us of an essential truth: to carry a baby is to carry forward a culture, a language, and a living heartbeat of community.

West Africa

Among West African peoples such as the Yoruba, Ewe, and Akan, the most widely used baby carrier is a simple, vibrant piece of cloth often called a kanga, lappa, or pagne. These large rectangular cotton cloths are celebrated for their bold colors and striking patterns, achieved through methods like wax-resist dyeing (batik), tie-dye (known locally as adire among the Yoruba), and hand-block printing. The dyes used often include deep indigos, sunny yellows, rich reds, and earthy browns, each chosen for both aesthetic beauty and symbolic power. Indigo, for example, has long been considered a protective color, linked to spiritual strength and resilience. Some kangas and lappas also include printed proverbs or blessings, offering wisdom or well-wishes to the wearer and child — a visual language of love and community.

In practice, mothers wrap the cloth around their torso and secure their baby high on their back, legs tucked, so the baby's body presses closely against them. The cloth is tied in a simple knot or tucked tightly at the front, creating a safe and comforting cocoon. This method keeps the baby calm and connected, allowing the mother to move freely through daily activities — whether working in the fields, preparing food, or visiting with neighbors.

The wrapper cloth is deeply embedded in West African life: it may later be used as a head wrap, a garment, or a ceremonial covering, symbolizing the seamless blending of care work, identity, and community belonging. In every fold and knot, we see the powerful message that carrying is not just practical — it is a living expression of love, heritage, and cultural pride.

A Yoruba mother carries her baby across the sand in Lagos, Nigeria, wrapped close in a bold printed cloth tied snugly across her back. Both wear crisp white—headwraps and dresses billowing with movement, echoing the traditions of coastal West Africa. The baby sits high and secure, legs tucked beneath the fabric and arms free to rest, eyes alert from the safety of this familiar position. The wrapper, a versatile length of fabric used daily by women across the region, is tied tightly over the mother’s chest, creating a firm seat without buckles or padding—just skill and practice passed through generations.

A mother from Senegal carries her child close in a brightly coloured wax print wrap — a style instantly recognisable across West Africa. The child rests calmly against her back, secured high with legs tucked under the fabric and arms free. Her gaze is direct and curious, adorned with tiny jewellery and a pink flower in her hair, echoing the vivid palette of her mother’s clothing. This common back carry is not just practical, but deeply cultural: woven into the everyday rhythms of life, storytelling, and connection. The print patterns and bold colours are more than decoration — they’re threads of identity, heritage, and pride.

A Fulani woman from West Africa walks confidently along a rural path, balancing a large bowl on her head while carrying her baby securely at her side. The child is wrapped snugly in a length of vibrant patterned fabric tied across the mother’s torso and hip, cradled in a semi-reclined position close to her body. This method, often used by Fulani and other Sahelian communities across countries like Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, allows caregivers to breastfeed or soothe infants on the move while continuing daily work. The woman’s colourful dress and headwrap reflect the rich textile traditions of the region, where bold prints and expressive adornments are part of cultural identity. Her joyful expression and upright bearing convey a sense of pride and ease, embodying the strength and rhythm of motherhood across the drylands of West Africa.

In a sunlit street scene from West Africa, mothers move through the marketplace with their babies carried securely on their backs in colourful woven cloths. Each wrap is tied high and snug, supporting the child’s body from knee to neck, with fabric deeply anchored beneath their bottom — a style passed down through generations. The patterned textiles — bold spirals, leafy prints, and bright contrasts — reflect the vibrancy of the region’s cultural expression. Even in the bustle of daily life, these carriers hold more than just weight; they hold rhythm, connection, and community.

In this striking image, a Tuareg mother from Niger carries her child across the desert landscape. Both are veiled in lightweight white cloth embroidered with bright florals, their shared covering shielding them from sand and sun. The baby is held high and close in a sturdy torso carry using a richly coloured woven cloth. This style of babywearing is common across nomadic communities in the Sahel, particularly among Tuareg women who traditionally blend functionality with artistry in their textiles. The layered fabrics speak to both protection and connection — each fold a gesture of care in a land where mobility and closeness are essential.

Along the banks of the Niger River, a woman strides forward with strength and grace, carrying a bundle of thorny branches high on her head and her child securely on her back. The baby is wrapped snugly in a length of indigo-dyed cloth, a style seen across parts of Mali and the Sahel. Tied firmly beneath the child’s bottom, the wrap provides both support and closeness, allowing the caregiver to carry on with essential daily tasks while keeping her child connected to her rhythm. This moment captures the resilience and continuity of traditional life in West Africa.

In the lush, green landscape of Sierra Leone, a woman tends to her garden with her baby carried closely against her back. The child is held in place by a vibrant cloth, knotted securely across the mother’s chest, in a style commonly seen throughout West Africa. Her posture is relaxed yet purposeful, the baby’s arm draped trustingly across her shoulder. Surrounded by palm trees and thick vegetation, this scene reflects a rhythm of life where caregiving and labour move together, woven into the land and the cloth alike.

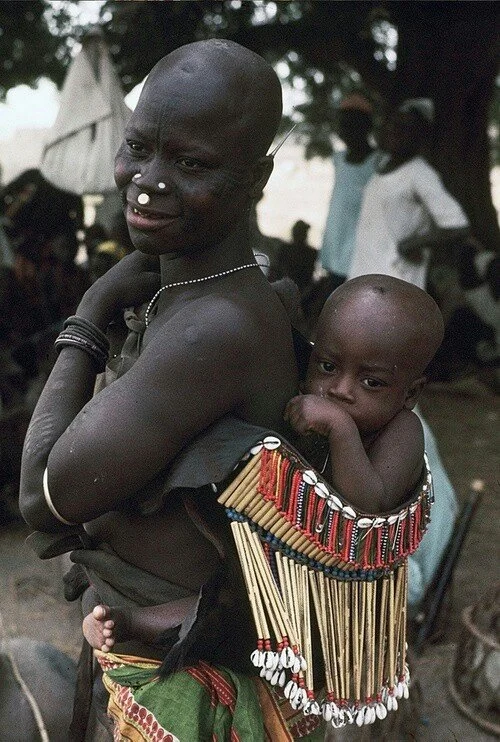

A woman from the Wodaabe (Bororo Fulani) people carries her baby high on her back, secured in place with a cloth and adorned beaded harness. The structured frame features rows of sticks, beads, and cowrie shells — both decorative and symbolic. Her skin is marked with traditional white facial dots, and her expression is calm and confident as she turns slightly toward the camera. The baby, bare and close, rests one arm around her shoulder. This striking image captures the cultural distinctiveness of the Wodaabe in Niger, where adornment, body art, and mothering are intimately intertwined.

East Africa

In East Africa, particularly along the Swahili coast in Kenya and Tanzania, mothers often carry their babies using the iconic kanga — a lightweight, rectangular cotton cloth that is as much a cultural statement as it is a practical tool. Unlike the heavier wax prints found in West Africa, the kanga is soft and airy, perfectly suited to the warm coastal climate. Each kanga features a bold central design, a richly decorated border, and, most distinctively, a printed proverb or saying known as jina. These messages range from blessings and words of encouragement to cheeky jokes and social commentary, creating a visual conversation between women and their community.

Mothers wrap the kanga securely around their torso, tying or tucking it to hold their baby high and snug on their back. The baby rests close against the mother’s body, feeling her warmth and hearing her heartbeat as she moves through her day — whether working, visiting neighbors, or attending community gatherings.

The kanga’s versatility goes beyond babywearing: it can become a head wrap, a skirt, or a ceremonial covering, embodying the seamless blend of care, identity, and expression. In each carefully chosen pattern and proverb, we see a celebration of motherhood, resilience, and the quiet power of women’s voices woven into everyday life.

In a maternity ward in Tanzania, a mother holds her newborn twins skin-to-skin using a length of brightly patterned kanga cloth, tied securely around her chest. The babies, wearing hand-knitted hats, are nestled upright against her body — a practice known as kangaroo care, widely encouraged for preterm or low birth weight infants. Her gaze is soft and centred on her babies, while another mother rests in the background. This image reflects both traditional carrying knowledge and the adaptation of cultural babywearing methods in clinical care to support early bonding and survival.

In the dry, open landscape of northern Kenya, a Somali mother carries her child on her hip using a striped shawl knotted tightly across one shoulder. Her vibrant red wrap dress and layered fabrics offer both protection and expression, blending practicality with beauty in a harsh climate. The child sits high and secure, one arm draped around her neck, their bond clearly evident. This carry style, often seen across the Horn of Africa, reflects a deep, intuitive knowledge of how to balance work, movement, and closeness — even in the most arid and demanding environments.

A mother in coastal Kenya carries her sleeping child close against her back, wrapped securely in a patterned kikoy tied across her chest. The child’s legs straddle her waist, resting in deep sleep with their cheek nestled into her shoulder. The soft earth tones of the cloth and her boldly patterned kanga skirt speak to the vibrant visual language of the Swahili coast, where generations of caregivers have used locally woven cloths for both adornment and nurture. Her hand rests on a walking stick, pausing for a moment as the child slumbers in the familiar rhythm of movement and rest.

Wrapped in vivid colour from head to toe, this mother carries her child snugly against her back beneath a rainbow-striped shawl. A second cloth, tied securely around her waist, holds the child high and close in the traditional East African style. The child peers out from the folds of the fabric, wide-eyed and alert, tucked safely into the familiar rhythm of everyday movement. The brilliant textiles, layering both beauty and function, reflect a culture where fabric carries story, identity, and connection — woven into every step of daily life.

Draped in deep purple and adorned with striking beadwork, this Maasai mother carries her baby confidently at her side, held close in a simple yet effective shoulder carry. The cloth is expertly gathered and knotted over one shoulder, creating a secure pouch that cradles the child’s body while leaving room for movement and visibility. Her intricate earrings and layered necklaces reflect a rich tradition of adornment and cultural pride. The child's wide eyes take in the world from the safety of maternal arms, enveloped in colour, warmth, and belonging.

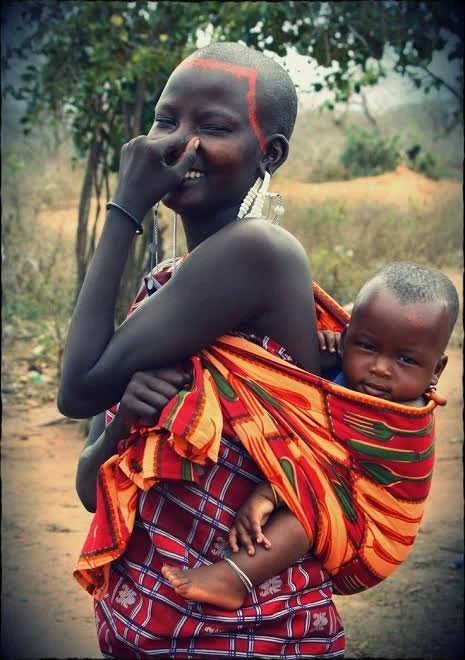

With warmth in her smile and intricate adornments reflecting her cultural heritage, this Maasai mother carries her child snugly in a boldly patterned kanga wrap. The cloth is wrapped high across her back and knotted securely at the front, creating a deep, hammock-like seat that supports the baby’s body from knee to knee. The baby rides alert and content, legs tucked around the mother’s waist in the classic position of closeness and security. Her shaven head, painted markings, and traditional jewellery speak to identity and belonging — this is babywearing woven into life and landscape.

In a gathering of vivid red, blue, and patterned cloth, Maasai mothers stand in community — each carrying their child close. The babies are nestled securely in wide wraps tied across their mothers’ backs, legs straddled and bodies upright, supported from knee to neck. Their sleepy heads rest gently against strong shoulders, protected and comforted by touch, rhythm, and presence. Beaded adornments and layered shúkàs reflect cultural pride and continuity. Here, babywearing is not just a practical tool — it is a way of life passed through generations, echoing identity, connection, and belonging.

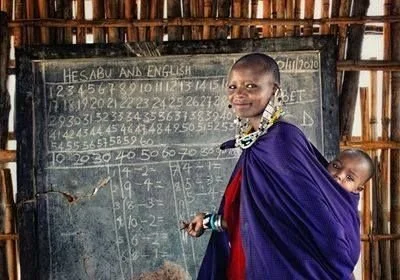

Wrapped in the rich purple fabric of her shúkà, this Maasai mother teaches in front of a chalkboard marked with numbers and English words. Her baby peeks over her shoulder, calmly observing from the snug cradle of the cloth on her back. The scene is a beautiful fusion of tradition and progress — education unfolding within the rhythms of caregiving. Beaded jewelry and cultural attire speak to her heritage, while the chalkboard reminds us that knowledge and nurture walk hand in hand. Here, babywearing supports not just the child, but a mother’s role as teacher, leader, and community guide.

With quiet confidence, this Mozambican mother meets the viewer’s gaze, her child carried close against her back in a bold yellow-and-green patterned cloth. The fabric is tied high and snug, creating a secure pouch that mirrors the way babies have been worn across Southern Africa for generations. Her child leans in with relaxed familiarity, nestled in a position that allows for comfort, connection, and mobility. On sandy ground under open sky, this moment captures the dignity of everyday care — rooted in cultural strength and passed through the hands of mothers who carry both children and community forward.

A young caregiver carries a sleeping child in a soft-structured back carrier made from animal hide, worn with the fur side facing out. The carrier hugs the child’s torso snugly, with a simple strap around the chest and narrow leather bands securing it across the caregiver’s shoulders. Small decorative charms hang from the top edge, catching the light as they move. A boldly patterned wrap cloth is tied at the waist, and brass bangles circle both wrists. The child rests quietly against the caregiver’s back — a portrait of calm, connection, and deeply rooted tradition.

A woman of the Mursi people of Ethiopia carries her baby high on her back in a wide cloth wrap, carefully tied to support the child’s weight. The cloth crosses over one shoulder and around her waist, forming a secure pouch for the baby, whose small foot peeks out from the folds. Her striking adornments include traditional lip plates, elaborate hair decoration with clay and plant material, and body scarification — all deeply significant within her culture. This moment captures the strength and dignity of a mother walking within her heritage, her baby close against her back as tradition and love carry forward together.

In a rural setting in South Sudan, a mother carries her sleeping baby wrapped snugly in a cotton cloth across her back. Tucked into a vibrant kitenge sling, the baby is shaded by a carefully positioned calabash gourd — a practical, traditional solution for long days under the sun. This striking image captures a moment of deep instinctive care, where the tools of daily life — cloth, gourd, wrap — come together in a simple but powerful expression of protection and connection. The use of calabash as a baby sunshade is a practice seen among Dinka, Nuer, and neighbouring groups, offering both shelter and continuity with ancestral ways.

Central Africa

In Central Africa, mothers carry their babies in simple but beautifully expressive cloth wraps, deeply adapted to the rhythms of forest and village life. Whether woven from cotton or crafted as traditional bark cloth among forest communities like the Mbuti, these carriers embody both practicality and deep cultural meaning. The cloth is tied high on the back, securing the baby snugly so they can sleep, watch, or nurse as the mother moves. Some cloths are decorated with bright prints or natural dyes, carrying patterns that speak to family ties and local identity. Among forest-dwelling groups, bark cloth carries spiritual significance and connects the child to their community and environment from the earliest days. In every fold, we see the quiet strength of mothers, weaving love, resilience, and heritage into daily life.

In the tropical forests of Central Africa, among the Twa people of the Democratic Republic of Congo, babywearing continues as an unbroken thread of maternal care and connection. In this photograph, a woman nurses her child in a boldly patterned cloth sling tied over one shoulder — a style deeply rooted in everyday life. The wrap cradles the baby in close, leaving both hands free while maintaining the rhythm of proximity that defines caregiving in these communities. Around her, other women sit with children nestled in laps or resting on backs, illustrating the communal nature of parenting where closeness, responsiveness, and tradition shape the early months and years of life.

Southern Africa

In Southern Africa, mothers often carry their babies using large, warm blankets — a practice deeply woven into daily life and ceremony alike. Among Zulu and Xhosa families, these blankets (sometimes called imbeleko) are not just practical tools but also important cultural symbols, used to introduce a baby to the ancestors and community. In Lesotho, the beautifully patterned Basotho blanket is both iconic outerwear and a cherished baby carrier, designed to keep little ones snug in the cold highland air. Babies are tied high on the mother’s back, wrapped securely so they feel her warmth and hear the rhythm of her heartbeat as she moves. Among San peoples, simpler cloth or skin slings have long kept babies close and safe during foraging journeys. In each community, these carriers speak of resilience, resourcefulness, and an unbroken bond between mother and child — a living tradition of carrying that nurtures both body and spirit.

In this striking image from Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), captured in 1960 by D’Lynn Waldron, a woman carries the layered weight of daily life with quiet strength and grace. A carefully balanced parcel rests on her head, while a young child is wrapped snugly on her back in a thick grey woollen shawl. In her arms, she cradles a small puppy — soft, warm, and just as carefully held. The rhythm of caregiving flows through her posture: calm, capable, connected. This is a portrait of nurture in motion, where babywearing is part of a broader expression of everyday love and responsibility.

A young mother from the Chewa people of Malawi sits resting, her child securely wrapped to her side in a patterned cloth tied across one shoulder. The baby’s upper body is supported snugly by the chitenje (traditional wrap), with their arms free and face turned outward in quiet curiosity. Decorative beaded necklaces adorn the mother’s neck, adding a personal and cultural flourish to her practical wrap. This common style of carrying allows for close contact while leaving the mother’s hands free — a familiar rhythm in everyday life across many parts of southern and eastern Africa.

In this extraordinary and intimate photograph by Frans Lanting, a mother in the Okavango Delta region of Botswana carries her child on her back as she wades into the water, skillfully maneuvering a large woven fishing basket. The child, securely tied against her with a simple cloth, nestles close, calmly watching and resting against her back while she works.

Her strong, upright posture and her beautiful, intricately styled hair reflect not just grace but also the remarkable physical strength and deep knowledge that mothers in many riverine and wetland communities embody. In this region, daily life is closely intertwined with water — fishing, gathering, and moving through shallow wetlands are integral to sustaining families.

The basket itself, masterfully woven from natural reeds, is a testament to local craftsmanship and resourcefulness. The mother’s ability to balance her work with the constant care and presence of her child illustrates a timeless, universal parenting instinct: to keep children close, safe, and fully included in daily rhythms.

This powerful image captures the resilience, skill, and quiet beauty of motherhood. It reminds us that carrying and caring are not separate from life’s work — they are deeply woven into every gesture, every breath, and every movement of a mother’s day.

This striking photograph shows a Samburu woman of northern Kenya carrying her baby using a traditional cloth tied around her body. The child is positioned on her front, resting comfortably against her chest, with the fabric pulled securely over the baby’s back and shoulders. The baby appears to be nursing, illustrating the close, responsive care typical of babywearing in many pastoralist cultures.

The carrier—a simple woven cloth—demonstrates the intuitive, adaptable nature of traditional carrying methods. It is knotted over one shoulder, crossing diagonally across the woman’s back, providing both support and easy access for breastfeeding. The baby’s legs are tucked beneath the fabric, in a secure and natural position.

The woman’s distinctive attire includes layers of bright bead necklaces, traditional head adornments, and bangles stacked on her arms—hallmarks of Samburu cultural identity. She also carries a blue woven bag on her back, showing how childcare is integrated with other responsibilities such as gathering or traveling. The dry red soil and open landscape behind her situate the image clearly in Kenya’s arid northern terrain.

This image captures not only a moment of nurturing connection, but also the strength, mobility, and dignity embedded in Indigenous East African babywearing traditions.

A Herero mother stands tall and serene beneath the Namibian sun, her baby sleeping soundly against her back, wrapped in a soft fringed cloth. Her striking attire reflects the unique cultural identity of Herero women — a deep red Victorian-style dress, flowing and full, reclaimed from colonial influence and worn now with pride. Around her neck, a vivid blue scarf adds contrast and grace, while atop her head sits the traditional otjikaiva, a sculpted headdress shaped like cattle horns — honouring the sacred role of livestock in Herero life. A quiet moment, rich in heritage and strength, captured amidst the everyday rhythms of a modern rural landscape.

Madagascar and Mauritius

While often thought of as distinct island cultures, Madagascar and Mauritius are part of Africa’s rich tapestry of babywearing traditions. Here, carrying practices beautifully reflect a blend of African, Austronesian, Indian, and European influences, all grounded in the shared value of keeping babies close.

In Madagascar, babywearing traditions center around the lamba — a versatile rectangular cotton cloth used for carrying babies on the back, as a shawl, or as ceremonial attire. Rooted in both African and Austronesian heritage, the lamba embodies the island’s unique cultural tapestry. Babies are tied close against their mother’s back, wrapped snugly so they can sleep or nurse while she moves through her day. In nearby Mauritius, a blend of African, Indian, and other influences has shaped carrying practices, with no single traditional style dominating. Historical use of simple cloth wraps can still be traced among older generations, though today many families use modern carriers influenced by global babywearing trends. Together, these island traditions reflect a shared value: keeping babies close, secure, and deeply connected to family life.

In this image, a mother from Madagascar carries her baby peacefully on her back, wrapped securely in a lamba — a traditional cloth deeply woven into Malagasy life. The baby sleeps soundly, held close and high against her back, sheltered within the mother’s movements and warmth. In Madagascar, carrying babies in this way allows mothers to move through daily activities, from market visits to farming and community gatherings, while keeping their little ones safe and comforted. The lamba is more than just a piece of cloth; it is a versatile, cherished garment used for carrying, clothing, and ceremonial purposes. This practice beautifully reflects the Malagasy belief that children belong in the flow of everyday life — embraced by family, tradition, and the heartbeat of the land.

In this vibrant and tender image, a young girl carries a baby securely on her back using a colourful wrap tied across her chest and waist. Likely captured in Madagascar — as suggested by the distinctive woven hats, earth-toned thatched architecture, and the kitenge-style fabric — this photo speaks to the communal, intergenerational nature of caregiving that is common in many African cultures.

Here, the responsibility of babywearing is shared not only among mothers but across siblings and extended family members. The wrap — often a single piece of cloth — is expertly tied, offering snug, upright support in a high back carry that keeps the baby's face visible, airway clear, and legs in a healthy, spread-squat position. The closeness fosters emotional bonding, body regulation, and security — all while the carer remains mobile and connected to daily life.

This image perfectly illustrates how babywearing is woven into the fabric of community, where carrying babies is not a burden, but a natural and honoured role — even for the youngest members of society.

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, babywearing traditions reflect the country’s deep spiritual heritage, diverse cultures, and strong communal ties. Across many regions, mothers and caregivers use wide cotton shawls known as netela or thicker gabi cloths to carry babies close to their backs or hips. These handwoven textiles, often white with colorful tibeb borders, are multifunctional — worn for warmth and modesty, during ceremonies, and transformed into baby carriers when needed.

Among the Hamar people of southern Ethiopia’s Omo Valley, mothers use carriers crafted from softened animal hide, adorned with cowrie shells and beads. These carriers cradle babies securely against the mother’s back, allowing her to work in fields, gather water, or take part in communal life while keeping her child close to her body and heart. Each shell and stitch holds protective and symbolic meanings, reflecting stories of beauty, ancestry, and care.

Whether swaddled in soft cotton or nestled in a beaded hide carrier, Ethiopian babies grow up immersed in the sounds of hymns, the hum of daily tasks, and the warmth of family closeness. To be carried in Ethiopia is to be enfolded in a living tapestry of tradition, love, and belonging from the very first days of life.

This image shows a mother carrying her child in a traditional way widely practiced in Ethiopia.

Ethiopian mothers often use a large, soft, woven cotton cloth called a shamma or netela, usually white with colorful decorative borders, to carry their babies. The wrap is tied securely over one shoulder and around the torso, creating a supportive seat for the baby on the mother’s back.

The baby’s position — high on the back, head peeking out and able to look around — reflects a cultural emphasis on connection and community observation, allowing children to see and engage with daily life from an early age.

This practice is a beautiful expression of Ethiopia’s deep cultural heritage, highlighting the close bond between mother and child, and the ways in which traditional textiles continue to play an important role in everyday life.

This beautiful image shows a mother from Ethiopia carrying her baby in a traditional embroidered cloth carrier. The carrier is richly decorated with beadwork and stitching, a style often seen in Oromo and other Ethiopian communities. The baby is worn high on the back in a soft structured pouch, securely wrapped and close enough to kiss.

The mother’s attire — including her intricate henna, gold accessories, and traditional dress — reflects Ethiopian cultural heritage, often worn during celebrations or formal occasions. Her joyful expression and confident posture speak to the strength and pride woven into caregiving traditions passed down through generations.

In this image, a Hamar mother from southwestern Ethiopia carries her baby in a beautifully crafted hide carrier, adorned with rows of cowrie shells. The carrier, worn across her back and shoulders, reflects both artistry and practicality, allowing the baby to rest deeply while she moves through her daily tasks. Among the Hamar, cowrie shells hold symbolic value, representing beauty, fertility, and social status. The mother’s ochre-twisted hair and layered beads further express her identity and connection to tradition. This deeply rooted carrying practice weaves together protection, cultural pride, and the belief that a child’s place is right at the center of community life — listening to the drumbeat of village songs and feeling each gentle sway of the mother’s steps.

This image shows a baby peacefully sleeping in a traditional animal-hide carrier worn by a caregiver from the Omo Valley in southern Ethiopia. The carrier is made from softened and patterned hide, shaped into a pouch and tied securely around the mother’s shoulder and torso. The baby's head rests snugly just beneath the shoulder line — protected, supported, and close.

Such carriers are characteristic of pastoralist groups in the region, including the Hamar, Banna, and Mursi peoples. Crafted from locally sourced hides and decorated with subtle markings or fringe, they reflect a deep relationship with the land and the animals they raise. This method of babywearing allows for hands-free caregiving, maintaining close contact while moving through daily life.

The Himba: Ochre Embrace and Desert Songs

In northern Namibia’s arid Kunene region, the Himba people are known for their striking beauty and deep connection to land and tradition. Himba women cover their skin and hair with otjize — a rich mixture of butterfat and red ochre — symbolizing earth’s life-giving power and offering protection against the harsh desert sun. This practice is a living expression of identity, resilience, and pride.

When it comes to carrying their babies, Himba mothers use soft leather slings or simple cloths to secure their children on their backs. The baby is nestled close against skin warmed and scented by otjize, sharing in the mother’s heartbeat and the earthy fragrance of red ochre. As mothers walk across sun-bleached sands or tend to cattle and homesteads, their babies sway gently, learning the rhythms of the desert and the songs of ancestral winds.

Each wrap and knot is both practical and symbolic — an intimate dance of survival, protection, and deep maternal love. To be carried by a Himba mother is to be enfolded in the warmth of sun and earth, growing up within a moving sanctuary of ochre and song.

In this stunning contemporary photograph, a Himba mother from northern Namibia carries her baby close against her back, secured by a simple cloth or hide wrap. The baby’s tiny foot peeks out, while the mother’s strong arm gently adjusts the carrier, embodying the constant attentiveness and care central to Himba parenting.

The mother’s hair is styled in the traditional Himba way, covered in a mixture of ochre, butterfat, and herbs that gives it a striking reddish hue and sculptural form. Her skin is also coated in this protective ochre mixture, known as otjize, which serves both aesthetic and practical purposes — protecting from the harsh desert sun and signifying beauty and identity.

She wears elaborate adornments: heavy metal and shell necklaces, beaded jewelry, and a decorated belt — each piece reflecting cultural meanings connected to age, social status, and life stages.

The carrying style, with the baby nestled high and close, allows the mother to move freely through daily life while ensuring her child remains safe and connected. Among the Himba, children are deeply integrated into community life from birth, carried everywhere and included in all activities, fostering strong bonds and a sense of belonging.

This powerful image captures not only the practical act of carrying but also the grace, strength, and rich cultural identity of Himba women — a living testament to the universal instinct to keep our children close, heart to heart.

This striking image shows a Himba mother from northern Namibia carrying her baby wrapped snugly on her back. The baby is carried in a cloth with a leopard-like pattern, secured tightly around the mother's back. Layers of fur padding and leather beneath the fabric suggest both warmth and structural support, creating a secure and comfortable nest for the child. Decorative metal loops and ties hang from the wrap and garments, reflecting the integration of adornment and utility in Himba culture.

In this powerful and beautifully detailed photograph, a Himba mother from northern Namibia carries her young child against her back using a traditional leather carrier. The child’s small body leans closely into her, legs wrapped around her hips, held securely and comforted by her warmth and movement.

The mother’s skin and hair are coated in otjize — a striking red mixture of butterfat and ochre that protects against the harsh desert sun and signifies beauty, strength, and identity within Himba culture. Her intricately styled hair, adorned with ornaments and beads, indicates her age, status, and life stage.

The carrier itself is made of leather and adorned with shells and metal elements, showcasing both practicality and deep artistry. These handcrafted carriers are central to Himba mothering traditions, allowing women to move freely through their daily lives — gathering food, tending to animals, or socializing — while keeping their children close and secure.

The image powerfully captures not only the functional aspect of babywearing but also the aesthetic and cultural pride woven into every detail of Himba life. It is a radiant testament to the strength of motherhood and the universal human instinct to keep our children safe and close, rooted in love and tradition.

In this striking portrait, a Himba mother from northern Namibia carries her baby high on her back using a traditional leather and hide carrier. The baby's legs wrap naturally around her waist, held securely as they move together through daily life.

The mother’s hair, covered in a distinctive mixture of red ochre, butterfat, and herbs, reflects her Himba identity and life stage — a deeply meaningful and beautiful expression of womanhood and community belonging. Her adornments, including heavy metal and beaded jewelry and animal skin garments, signal both status and heritage.

The carrier itself, crafted from softened animal hides and often richly decorated, embodies practicality and cultural pride. It allows the mother to keep her child close, safe, and comforted while she carries out her work, symbolising the deep interdependence and connection between mother and child woven into Himba traditions.

The San

The San peoples (sometimes collectively referred to as Bushmen), include groups like the !Kung, G//ana, Ju/’hoansi, and others living across regions of Botswana, Namibia, Angola, and South Africa.

San mothers traditionally carry babies with minimal or no cloth, reflecting their forager lifestyle and warm, arid environment. Babies are often held directly on the hip or back, secured with a simple leather thong or soft hide strap, sometimes supported by a small fur or skin sling when traveling longer distances.

These carrying aids are minimal, designed to allow skin-to-skin contact and continual breastfeeding, and they reflect deep knowledge of both the land and body rhythm.

In the wide Kalahari sands and open bushveld, each simple hide strap and every gentle hip sway speaks of ancient rhythms and tender belonging. The San practice of carrying babies close, almost continuously, offers one of the most profound living connections to humanity’s original caregiving blueprint — an unbroken, sun-warmed embrace that whispers: you belong here, always.

A San mother carries her baby nestled against her back in the golden light of the Kalahari. The soft, weathered leather wrap — made from animal hide — is tied securely around her torso, holding her little one close as she walks through the dry brushland of southern Africa.

This simple but effective baby carrier reflects the ancient, continuous caregiving traditions of the San people, who are among the oldest known cultures on Earth. The baby's legs tuck in naturally, spine rounded in comfort, with their head resting peacefully near their mother’s shoulder. Her hands are free, her posture upright, and the wrap distributes weight evenly without buckles or fasteners — just traditional knowledge and practiced skill.

Everything about this moment speaks of belonging: to land, to lineage, and to each other. It's a moving glimpse into the enduring wisdom of Indigenous parenting, where closeness is not just a preference, but a way of life.

In this powerful image, a San mother — one of the Indigenous peoples of southern Africa — carries her baby in a simple animal skin sling, secured over one shoulder and wrapped around her body. This style of babywearing reflects millennia of caregiving knowledge passed down through generations of hunter-gatherers who have long lived in the arid regions of the Kalahari Desert.

The baby rests high on her back, peeking calmly over the edge of the soft hide. The wrap hugs them close, offering security, warmth, and ease of movement for the caregiver. Other women and children in the background wear similar garments and carriers, echoing a shared rhythm of life where closeness and community underpin everyday survival.

This image captures the intimacy and resilience of San family life — where mobility, connection, and instinctive parenting are deeply interwoven. It's a reminder that some of the oldest known human caregiving practices are still alive in the arms — and slings — of today’s Indigenous mothers.

A San child peers out from the safety of their mother’s back, cradled in a timeworn leather sling that has carried generations before them. The wrap is anchored high over one shoulder, knotted securely with a strip of the same hide — no buckles or straps, just traditional skill and the rhythm of everyday life.

Their eyes meet the camera with quiet curiosity, while one small hand rests gently on their mother’s side. There is closeness, comfort, and connection in every detail. The carrier is shaped not only by its material, but by centuries of embodied knowledge — adapted to this land, this climate, this way of moving together.

In this powerful image, a San mother walks through the sunlit grasses of the Kalahari, her young child securely tucked against her chest. The baby's limbs are relaxed, head resting softly near her heart, wrapped snugly in a garment fashioned from what appears to be soft animal hide or woven cloth. There is no fancy construction — just skilled folds, deep instinct, and the confident ease that comes from generations of practice.

The San people — often referred to as Bushmen — are among the oldest continuous cultures in the world, with a deep history of living in intimate relationship with their land. Their parenting is grounded in constant physical closeness and responsiveness, hallmarks of a traditional babywearing culture. Here, we see that philosophy embodied: the mother’s upright posture, the baby's calm gaze, and the shared rhythm of their movement across the dry savanna.

Despite the arid backdrop, there is a sense of quiet strength and continuity. The carrier is not an added device — it is part of the clothing, the body, the way of life. This image captures the essence of ancestral caregiving: connected, adaptable, and deeply human.

The Hadzabe

In the dry savanna and baobab-dotted woodlands surrounding Tanzania’s Lake Eyasi live the Hadzabe — one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer peoples of Africa. Deeply attuned to the land and its seasonal rhythms, the Hadzabe move lightly across their territory, guided by ancestral knowledge of plants, animals, and the shifting winds.

When it comes to carrying their babies, Hadzabe mothers use simple cloth wraps or softened animal skins, securing their children close against their backs. The baby is held snugly, resting in the gentle sway of each footstep, wrapped in the warmth of skin and the soft scent of wild honey and wood smoke that cling to a mother’s body.

As mothers gather tubers, berries, or baobab fruit, or move silently on the trail of honeyguide birds, their babies learn the textures of the earth and the cadence of foraging songs. Each movement is an invitation into a world where every rustle and chirp holds meaning, and each shared breath strengthens the unbroken line between generations.

Every tie and twist of the cloth is a quiet act of devotion — a testament to resilience, freedom, and profound connection to the land. To be carried by a Hadzabe mother is to be cradled by the rhythm of the savanna itself, growing up in harmony with the pulse of wind, thorn tree, and sun.

Make it stand out

In this intimate image, a Hadzabe mother from northern Tanzania cradles her baby close against her back, wrapped securely in a brightly patterned cloth. The vivid greens, golds, and reds of the kanga echo the warmth and vitality of the landscape, and the baby’s wide, curious eyes seem to take in every detail of the world unfolding around them.

The cloth is tied snugly across the mother’s chest and shoulders, a practical and loving gesture repeated countless times each day. As she moves, her baby is rocked gently by the rhythm of her steps and the hum of her voice — a living cradle shaped by breath and movement.

In this image, a Hadza mother from northern Tanzania shares a radiant, joyful moment with her baby, carried close in a colorful kitenge cloth tied across her chest. The baby leans forward curiously, watching as the mother gathers wild berries — a daily rhythm that connects the family to the land. Among the Hadza, one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer peoples in Africa, children are carried almost constantly, included fully in the movements and sounds of foraging life. The mother’s bright smile and the baby’s attentive gaze reflect a deep, shared learning and a trust built through continuous closeness. Here, the wrap becomes more than a tool; it is a living bridge between mother, child, and the wild, sustaining landscape that supports their community.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.