Mediterranean Europe: Olive Groves and Sunlit Cloth

In the warm, sun-soaked regions of Mediterranean Europe — from Greece and Italy to Spain and the coastal villages of the Adriatic — babywearing traditions reflect a life lived in close connection with family, land, and the rhythms of the seasons.

Throughout rural Mediterranean communities, simple woven cloths, shawls, or large scarves have long been used to carry babies on the hip or back while caregivers tended olive groves, vineyards, and small gardens. Babies nestled into the scent of earth and wild herbs, lulled by the sound of cicadas and the hum of family voices echoing through stone courtyards.

In Greece, women often used long rectangular cloths, sometimes repurposed from everyday garments, to tie babies close while gathering water or preparing food in communal outdoor kitchens. In Italy, especially in southern regions and island communities, mothers carried babies as they harvested grapes or cared for livestock, the infants learning dialects and songs with each gentle sway.

In Spanish villages, brightly colored shawls and mantones served multiple purposes — warmth, modesty, and as baby carriers. Babies were brought along to fiestas, religious festivals, and market days, included in the vibrant tapestry of daily life from their earliest moments.

These carriers were more than practical tools; they were expressions of resourcefulness and care, embodying the belief that a child belongs in the arms of the community rather than set apart.

The 20th century brought significant shifts, with prams and modern childcare ideals replacing traditional methods. Yet in many rural and island areas, elders continued to pass down cloth carrying techniques, maintaining a quiet thread of continuity through changing times.

Today, as Mediterranean families and communities renew their interest in local textiles and ancestral practices, there is a gentle revival of babywearing as a celebration of slowness, connection, and deep-rooted belonging.

To be carried in Mediterranean Europe is to feel the sun on woven cloth, to hear lullabies drift between olive trees, and to be folded into the enduring warmth of family and land.

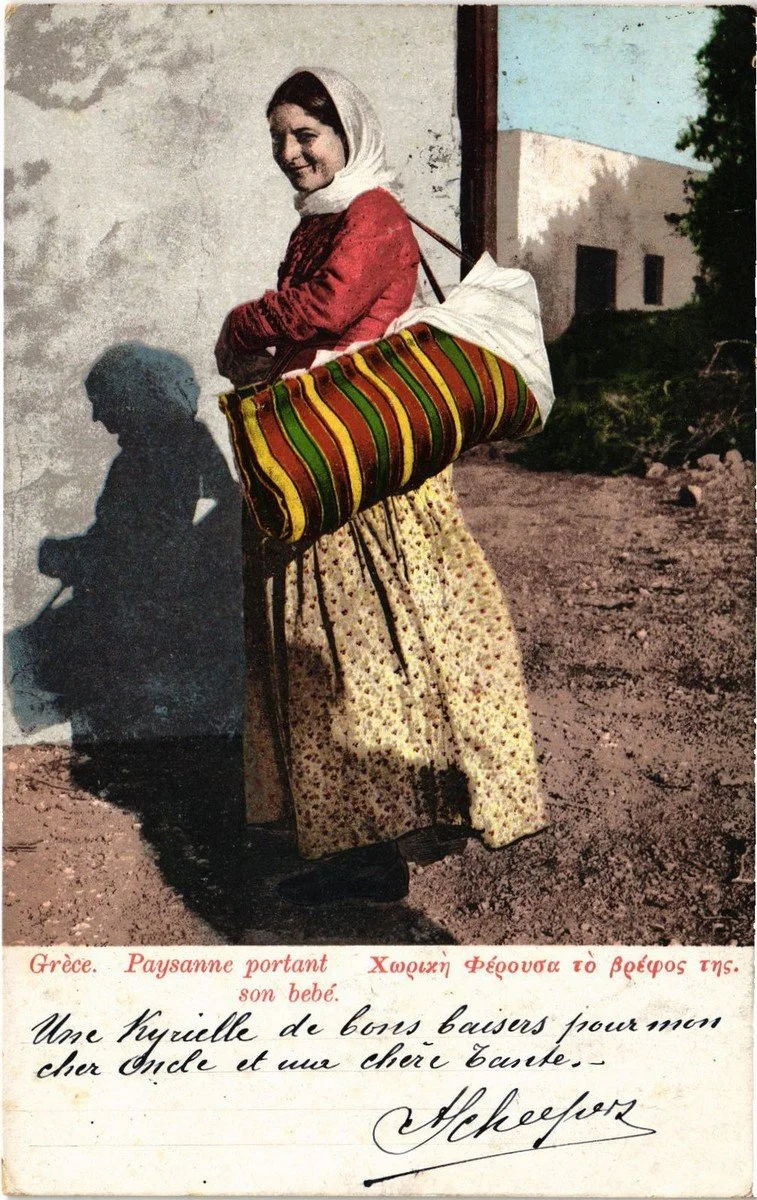

This vintage postcard from Greece depicts a peasant woman carrying her baby in a traditional cradleboard-style carrier. Instead of a soft wrap or cloth, the baby is secured inside a structured, padded bundle, worn across the mother's back like a large, colorful pillow. This method allowed mothers to keep their infants safe and comfortable while working outdoors or traveling between villages. The bright striped fabric and floral skirt highlight regional textile traditions, and the woman’s serene smile reflects the pride and warmth woven into daily life. This striking image offers a glimpse into rural Greek mothering practices in the early 20th century, showcasing both practicality and cultural identity.

A woman stands spinning wool with a drop spindle, her hands steady in motion as the fibres twist between her fingers. She wears dark layered clothing and a shawl drawn over her head and shoulders, the folds heavy but familiar. On her back, a baby is carried upright, nestled securely in fabric tied around the mother’s torso and gathered high enough for the child to see the world from over her shoulder.

This is rural Portugal, most likely from the early 20th century. The woman’s wooden clogs and the traditional spindle work — once common across the Iberian Peninsula — speak of mountain villages and generations of women who worked with both fibre and child on their body.

There is no separation between care and craft here. The baby is carried close, wrapped into the rhythm of the day, into the long thread of tradition. With each twist of the spindle, something is made — yarn, yes, but also warmth, closeness, and continuity.

A young nomadic woman stands outside a tent, her baby bundled in her arms, swaddled in layered cloth and held securely at her front. Her clothing is elaborate and textured — a richly embroidered vest, wide gathered skirt, and headscarf tied low across her brow. Beaded jewellery and a thick belt complete the outfit, marking both cultural identity and personal adornment.

The baby’s head is wrapped for warmth, and though not fully visible, the position suggests a wrap or wide shawl used to support the weight as she stands. Behind them, the dark canvas of the tent provides a backdrop of daily life on the move — buckets, fabric, straw underfoot.

The text confirms the location: Macedonia, northern Greece, and identifies the subject as a “Jeune Nomade” — a young nomadic woman. Likely of Vlach (Aromanian) or Sarakatsani heritage, both pastoralist groups known for seasonal movement and distinctive dress, she stands with quiet pride, baby in arms, fully present in the landscape she calls home.

This is babywearing as part of survival and belonging — layered into the clothing, into the journey, into the identity of a people always moving, always carrying.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.