Arctic: Northern Lights, Soft Skins, and Silent Strength

Arctic babywearing traditions

Across the circumpolar north — from Sámi lands in northern Europe to the coastal Inuit communities of Greenland and Alaska, and the vast tundras of Siberia — babywearing practices have been shaped by cold, movement, and deep connection to land and animals.

These carriers, whether fur-lined komse cradles, moss bag wraps, or amauti parkas, reflect a shared need to protect babies from harsh climates while keeping them close to the warmth and heartbeat of their caregivers. While each community’s designs and materials differ, all carry the same spirit: love, survival, and continuity.

In these regions, babywearing is not just a practical necessity — it is an intimate, embodied relationship between caregiver and child, woven through the rhythms of daily life on snow-covered trails, reindeer herding camps, and icy coastal hunting grounds. Babies are held within soft skins and furs, their faces protected from biting winds, yet able to watch, listen, and learn from the world around them.

Each stitch and wrapping technique reflects generations of adaptation, resilience, and care. These carriers are more than tools; they are living expressions of cultural knowledge and silent strength, shimmering quietly beneath the northern lights.

Inuit (Canada & Greenland)

Among the Inuit of Canada and Greenland, babywearing is most beautifully expressed through the amauti, a parka with a special built-in baby pouch beneath a large, protective hood. The baby is carried high on the mother’s back, close to her body for warmth, yet able to peek out over her shoulder to see the world.

The amauti’s soft skin or cloth lining and wide hood shield the baby from icy winds and snow, allowing mothers to continue hunting, fishing, and traveling across frozen landscapes. The shape and decorations of the amauti vary by region and family, but all reflect a deep commitment to keeping babies safe and connected to community life.

Wearing an amauti is not just practical — it is an expression of love, resilience, and cultural identity, passed down through generations like a living, fur-lined embrace.

This joyful scene shows an Inuvialuit or Inuit grandmother carrying her grandchild in a traditional amauti — a beautifully crafted parka designed for carrying children in Arctic regions.

The child sits snugly in a large back pouch, close to the caregiver’s warmth and heartbeat. The hood can be pulled up to shield them completely from the harsh wind and snow, a brilliant adaptation for life on the tundra.

The grandmother’s gentle expression and the child’s wide smile embody the timeless bond and generational care that babywearing supports. Even today, these practices remain vital, linking modern life with ancestral knowledge and resilience.

In this joyful portrait, an Inuit mother wears a traditional amauti, her child peeking out from the wide, protective hood.

The amauti is an extraordinary parka unique to Inuit mothers, designed with a deep back pouch that cradles the baby against her warmth. The large hood can be adjusted to cover both mother and child, shielding them from icy winds while allowing the child to look out and feel part of the world.

This carefully sewn garment, often decorated with subtle details and trims, reflects deep ancestral knowledge of skin sewing and Arctic survival. It embodies the close, continuous contact so central to Inuit parenting — keeping babies safe, loved, and part of daily life on the land.

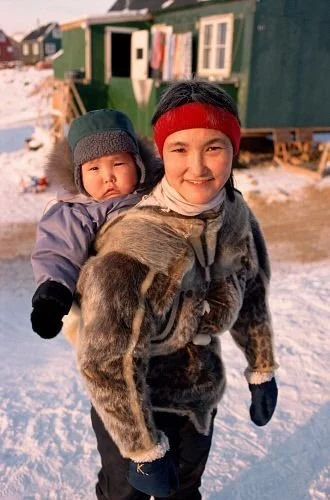

In this vibrant modern image, two Inuit women stand side by side wearing traditional amautiit — beautifully crafted parkas designed specifically for carrying children. The woman on the right has her child safely nestled in the large, soft back pouch of her amauti, the child peeking out over her shoulder with a curious gaze.

Made from warm, supple sealskin or caribou hide, amautiit are perfectly adapted to Arctic life, allowing mothers to keep their babies close to their body heat and protected from harsh winds. The large hood can be pulled up to shelter the baby entirely, while the wide shoulders and gathered back create space and security.

These garments are a powerful expression of skill, care, and cultural continuity. This photograph beautifully illustrates how traditional knowledge and design remain deeply alive today, connecting generations through warmth and love.

In this radiant winter portrait, a Greenlandic Inuit mother beams warmly as she carries her bundled child on her back. The child is securely nestled inside the mother’s amauti, a traditional fur parka ingeniously designed to shelter children from Arctic winds while keeping them close to their caregiver’s warmth.

The mother’s smile and the child’s watchful eyes tell a story of resilience and joyful connection, even in the harshest environments. Behind them, colorful houses stand stark against the snowy landscape, emphasizing the vibrancy of community life in Greenland.

This image beautifully captures the enduring tradition of carrying — a practice that wraps babies in safety, love, and the ever-present embrace of the north.

This joyful contemporary photograph shows an Inuit mother wearing her child in an amauti — a traditional women's parka designed with a large hood and pouch for carrying babies on the back.

The amauti’s ingenious design keeps the child close to the mother’s body for warmth and protection, while allowing the mother to move freely in harsh Arctic conditions. The large, fur-lined hood can be pulled up around both faces, creating a shared shelter from wind and cold.

Iñupiat and Yup’ik (Alaska)

Among the Iñupiat and Yup’ik peoples of Alaska, babies have long been carried in fur and skin parkas, similar to the Inuit amauti but adapted to local lifeways and materials.

Mothers place their babies inside the large back of the parka, often with added moss or fur padding for warmth and comfort. The baby sits close to the mother’s body, sharing her warmth while being protected from harsh coastal winds and long journeys across sea ice or tundra.

Carriers and wrappings are decorated with beadwork, animal fur trim, and symbolic stitching, each detail offering protection and connection to family stories. This way of carrying is a testament to the quiet strength and ingenuity of Arctic mothers, whose love and skills shape each stitch and tuck of fur.

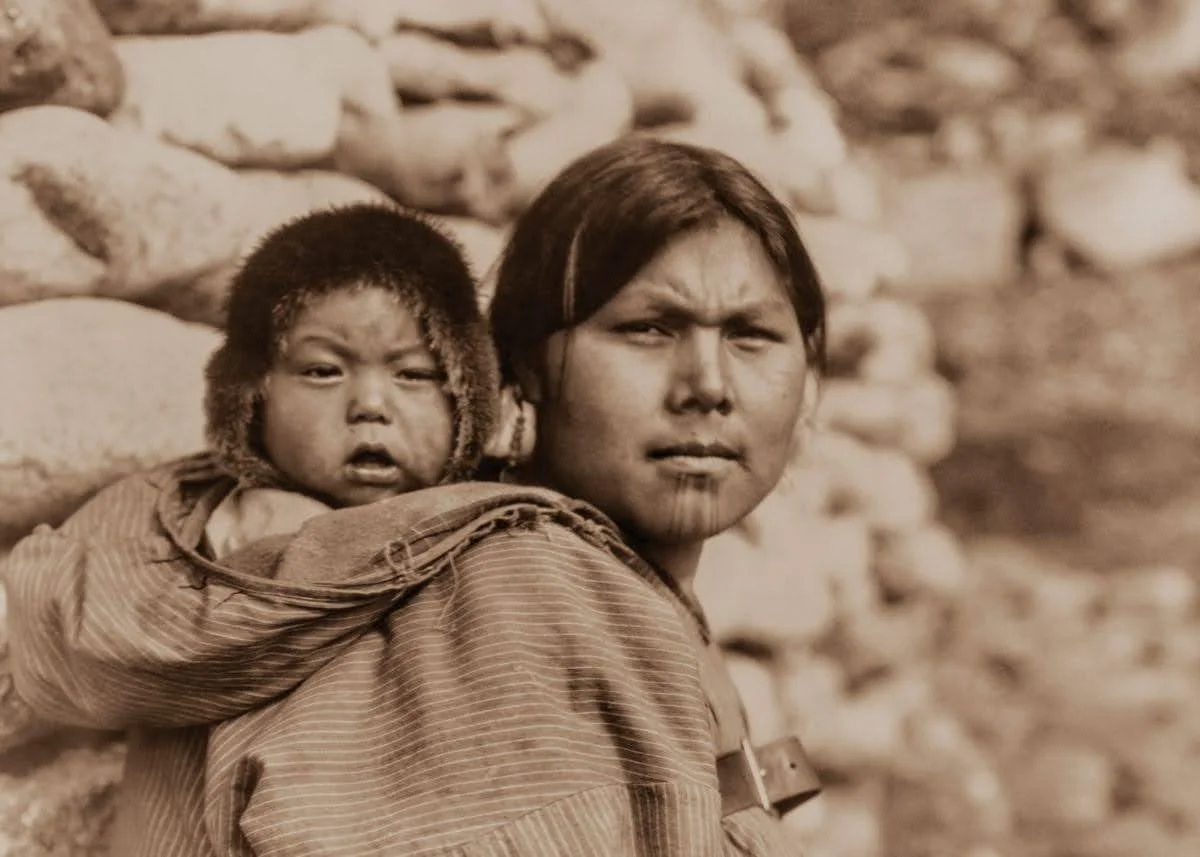

In this striking historical portrait, a mother from Little Diomede Island, Alaska, carries her child high on her back. The child, bundled warmly in a fur-lined hood, peers out with a calm, watchful gaze. The mother’s face is steady and strong, adorned with traditional chin tattoos — markings deeply meaningful in many Indigenous Arctic cultures, often signifying family lineage, life milestones, or personal achievements.

She wears a thick, striped garment wrapped and tied securely, keeping her baby close and protected against the harsh northern environment. This style of carrying, common among Inuit and other Indigenous Arctic peoples, exemplifies adaptation to extreme cold and the deep bond between mother and child.

This image was captured by Edward S. Curtis, a photographer known for his extensive — though often romanticized and staged — documentation of Native American and Indigenous Arctic communities in the early 20th century. While Curtis’s photographs are valuable records, it is important to approach them critically, acknowledging that subjects were sometimes posed or described in ways that did not fully honor their lived realities.

Despite this, the photograph radiates resilience and connection: a testament to the enduring strength of Indigenous families and the universal instinct to keep our little ones close and safe.

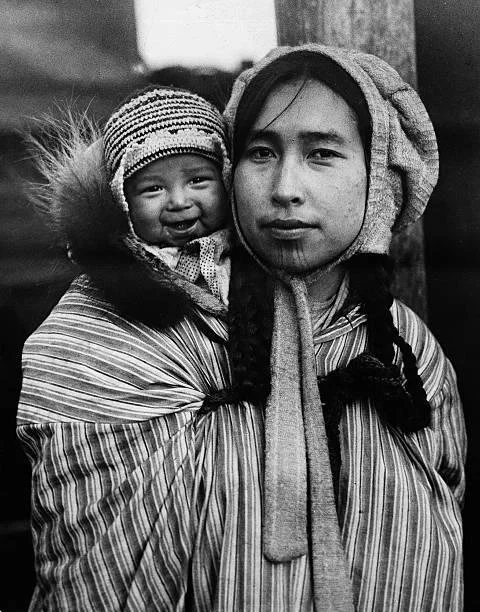

In this striking historical portrait from 1927, an Inuit mother at Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, carries her child high on her back. The child, warmly bundled with a fur-lined hood, peers out over her shoulder with a calm and watchful gaze, taking in the snowy world beyond.

The mother’s thick, striped textile wrap is secured carefully, exemplifying the sophisticated techniques developed to protect babies in Arctic conditions. By holding the child close to her body heat, she ensures warmth and comfort even during long travels or harsh weather.

Her steady expression reflects quiet strength and deep devotion — a universal language of motherhood that transcends place and time.

This photograph captures more than a moment: it embodies the enduring resilience, skill, and love that define Inuit family life, passed through generations beneath the northern lights.

This beautiful historical photograph shows an Inuit mother, likely from Alaska or northern Canada, carrying her baby in a traditional amauti, a fur parka specially designed to keep little ones warm and close in Arctic conditions. The baby peeks out from the generous hood, safe against her mother’s body and able to share in her view of the world. Her gentle expression, the baby’s calm gaze, and the resting dog beside her all evoke a profound sense of warmth, connection, and community. The amauti’s expert construction, using animal skins and fur, reflects generations of wisdom and intimate knowledge of the land. This image beautifully captures babywearing as a timeless act of love, adaptation, and cultural continuity."

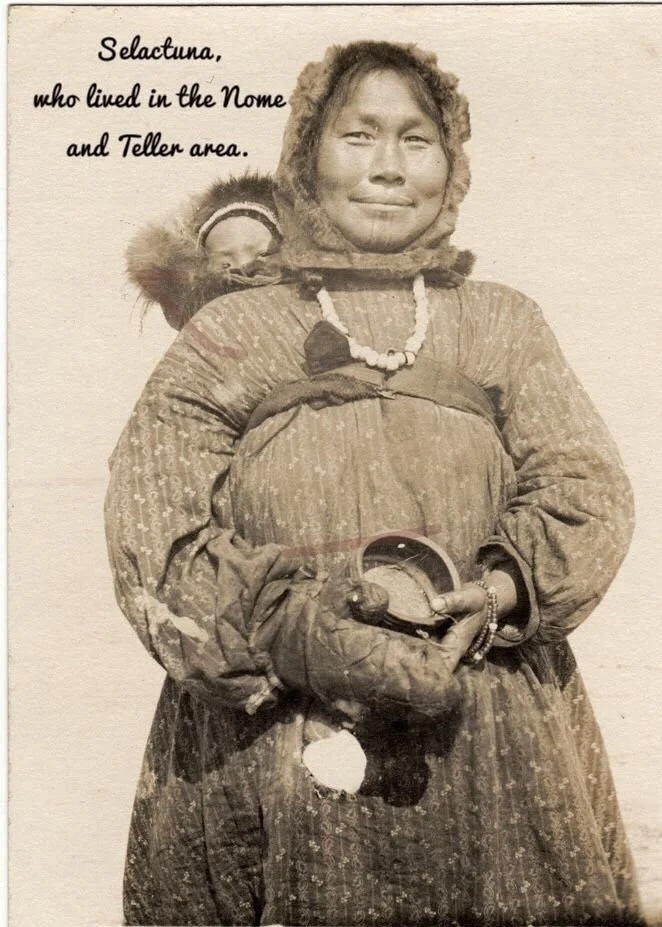

This historical photograph shows Selactuna, an Indigenous Iñupiat woman from the Nome and Teller area of northwestern Alaska. The sepia-toned image likely dates to the late 19th or early 20th century, a period of rapid change and colonial contact in Alaska. Selactuna stands facing the camera, smiling softly, dressed in a long, quilted garment suited to the harsh Arctic environment. Her hands, protected by thick mittens, hold a small bowl — possibly used for food, grinding, or ceremonial purposes.

Peeking just over her shoulder, framed by the fur-lined hood of her parka, is a baby — likely her child or grandchild — carried in a traditional parka carry. Among the Iñupiat and other circumpolar Indigenous groups, babies were often placed inside the large hood or back panel of a mother’s or caregiver’s parka. This clever design, built into the garment itself, allowed infants to be protected from cold, wind, and snow, nestled securely against the adult’s body for warmth and bonding.

Sámi (Northern Europe)

In Sápmi, the homeland of the Sámi people across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, babies are traditionally carried in the komse — a wooden cradle lined with soft furs.

The komse is shaped like a small boat or sled, with high protective sides and a rounded hood to shield the baby from snow and wind. Infants are wrapped snugly in layers of reindeer fur and cloth, then tied securely into the komse before it is carried on the mother’s back, pulled on a sled, or propped nearby while tending reindeer or working.

Bright ribbons, embroidered cloth, and protective amulets often decorate the komse, weaving together warmth, spirituality, and cultural pride. Each cradle is a moving sanctuary, a place where Sámi babies learn the rhythms of the tundra and the songs of their ancestors from their first breath.

Among the Sámi people of the far north, babies are carried in beautifully crafted cradleboards called komse, wrapped in furs and love against the Arctic winds. Here, a mother holds her child nestled in a komse, her traditional dress echoing the forest around her. Each stitch and wooden curve tells of a deep bond with the land and ancestors, a promise of safety even in the coldest seasons. As mothers travel across snowy tundras and birch forests, babies rest securely, learning from their earliest days the heartbeat of reindeer herds and the whisper of the northern lights above.

This photograph shows a Sámi mother holding her baby in a traditional komse, the cradleboard used by Sámi families of northern Scandinavia. Made from wood and lined with soft materials, often reindeer fur, the komse keeps babies secure and warm even in the harsh Arctic climate. The protective arch and tied laces allowed Sámi parents to carry, sled, or wear the cradle as needed — an ingenious design shaped by centuries of life close to nature. The mother’s attire, with its decorative woven bands and practical layers, reflects the distinctive textile traditions of the Sámi. This image is a beautiful testament to Indigenous babywearing practices, showing how deeply practicality, connection, and cultural identity are woven together in caring for the youngest members of the community.

This historical photograph shows a Sámi mother proudly holding her baby in a traditional komse, or cradleboard. Beautifully adorned with patterned woven bands and protective arches, the komse is designed to keep Sámi babies safe and warm in harsh Arctic conditions. The mother’s attire — layered woolens, intricately woven belts, and decorative jewelry — reflects Sámi traditions deeply tied to both function and cultural expression. The rich colors and symbolic motifs in the textiles celebrate Sámi identity and family heritage. This image powerfully captures how Sámi families have long integrated babywearing into daily life and seasonal migrations, weaving together practicality, artistry, and deep connection to land and community.

This portrait of a Sámi family showcases the deep cultural roots and skilled craftsmanship of northern Scandinavia’s Indigenous people. The mother holds her baby in a beautifully decorated komse (also called gahkku or cradleboard), traditionally used by Sámi families to keep infants safe and secure. Intricate beadwork and woven straps demonstrate the care and artistry passed down through generations. The family’s richly patterned clothing further highlights their heritage, blending practicality with striking design. This image celebrates the warmth, resourcefulness, and strong family bonds that define Sámi life.

In this evocative hand-colored photograph taken around 1900, a Sámi family is gathered outside their traditional tent dwelling (lavvu or goahti) in northern Scandinavia. At the center, a woman holds a cradleboard (komse), a distinctive Sámi baby carrier designed to keep infants swaddled and warm. The komse is shaped almost like a boat, often lined with reindeer fur, and sometimes adorned with protective amulets or colorful embroidery. It could be carried on the back, placed on a sled, or suspended from a branch to rock the baby gently, allowing caregivers to continue daily work while keeping the child close.

In this beautifully colorized photograph, a Sámi mother gently rocks her baby in a traditional cradleboard, known as a komse or komsai. The cradleboard is suspended from a birch tree, transforming it into a natural swinging cradle — a practice that soothes the baby and keeps them safe while the mother works nearby.

The baby is carefully wrapped in warm layers and secured with bindings and a protective arch, reflecting the Sámi people's deep knowledge of their northern environment and their adaptive parenting traditions. The mother wears a gákti (traditional Sámi dress), adorned with distinctive woven and embroidered bands, signaling her cultural identity and possibly her family or regional ties.

In this vibrant contemporary photograph, a Sámi woman dressed in striking traditional gákti carries a cradleboard known as a komse or komsai. Her attire — with its bold blue, red, and gold hues, intricate embroidery, and elaborate fringed shoulders — proudly signifies Sámi cultural identity and craftsmanship.

The komse she holds is carefully covered with a richly patterned red cloth, protecting the baby inside from wind and chill while adding to the visual celebration of Sámi textile tradition. This cradleboard style keeps the baby securely swaddled and close, embodying both care and practicality as the Sámi move through their northern landscapes.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.