Ultraprocessed Babies

If all our actions as parents were driven simply by choice, then judgement might be justified. But so often, it isn’t choice that drives us — it’s circumstances. Information is not judgement. It isn’t personal. It’s something we can use to feel empowered when we consider the impact of our actions.

In the UK, just 1% of babies are exclusively breastfed at six months. That means 99% are fed some combination of infant formula, commercial infant foods, breastmilk, and family foods. Here in Australia the story is similar. We have one of the highest rates of breastfeeding initiation in the world, yet very few families continue exclusively to six months. Formula “top-ups” are often introduced in the first week, and many babies are given solids from around four months — commonly starting with rice cereal, itself an ultra-processed product.

The First 1000 Days

From conception to age two, nutrition shapes lifelong health. Ultra-processed foods in this window alter taste preferences and raise risks of obesity and chronic disease. But the barriers to reaching optimal nutrition guidelines are many.

Global Snapshots

Australia: high breastfeeding initiation, low exclusivity, early solids.

US: minimal maternity leave, formula use, weak regulations, heavy marketing.

Asia/South America: rapid growth in toddler foods, fortified pouches, toddler milks.

EU: stricter rules but loopholes exist.

Africa: vulnerable to aggressive formula marketing, despite WHO Code.

Infant Formula: The First Ultra-Processed Food

Infant formula is, by definition, an ultra-processed food. It is industrially manufactured from animal milk (or soy), broken down, stripped of natural qualities, then rebuilt with added oils, sugars, and micronutrients to approximate human milk. For some families, formula is necessary, even life-saving. But recognising its ultra-processed status matters — because it shows how deeply commercial food systems are embedded in infant feeding from the very beginning.

From Formula to Finger Foods: How Marketing Shapes Baby Diets

Once solids are introduced, the range of ultra-processed products grows rapidly. Pouches, teething biscuits, sweetened yoghurts, “iron-fortified” cereals, rice crackers, and toddler milks line supermarket shelves. Labels reassure us with claims like organic, made with real fruit, no added sugar, or fortified with iron. Yet these foods are designed for profit and convenience, not health. Behind the packaging, many are closer to confectionery than to the fruits, vegetables, grains, and legumes our babies really need.

The Snack Trap

Perhaps the most concerning products are the single-serve, grab-and-go snacks marketed to busy parents as healthy options. They come in bright packets and promise the goodness of fruit and vegetables, but a closer look at the ingredients tells another story.

Puffed and extruded snacks such as corn puffs, rice wheels, “veggie sticks” and teething crackers are mostly refined starches such as rice, corn, or potato. A token amount of powdered carrot, spinach, or beetroot is often added so the packet can claim “made with vegetables.” In reality, these snacks deliver almost none of the nutrients of the real foods they mimic.

Wet snack packs and pouches are another common example. Marketed as convenient ways to give children fruit and vegetables, most are built on a base of cheap apple or pear purée and juice concentrate. Small amounts of other fruits or vegetables are added so we believe our children are eating blueberries, kale, or pumpkin — but these ingredients are often present only in trace amounts. Many also contain thickeners, acidity regulators, or added starch to achieve the right texture and shelf life.

Sweetened yoghurts and “dairy snacks” aimed at toddlers frequently rely on added fruit concentrate and sugar. A product advertised as “no added sugar” may still be high in naturally concentrated sugars from fruit purées, creating a sweet product far removed from plain yoghurt or fresh fruit.

The packaging of these products tells a different story. Brightly coloured fruit and vegetables, smiling cartoon faces, and even characters from popular children’s television shows dance across the packets. They make lunchboxes look fun, healthy, and appealing. But inside, the actual foods usually cater to toddlers’ instinctive preference for bland, beige “safe foods” — high in carbohydrates, predictable in flavour, and easy to chew and swallow quickly.

When toddlers reject fresh whole foods (as many naturally do during phases of suspicion), we can easily interpret their eagerness for these packaged snacks as “preference.” In reality, what looks like choice is often a response to the engineered sameness of ultra-processed products — and the clever marketing that convinced us they were a healthy option.

Aisles of Promises

Standing in the baby aisle at any supermarket, you’re met with shelves packed floor to ceiling with pouches, cereals, snack bars, and tins of formula. Bright colours, smiling babies, cartoon animals and promises of “organic”, “no added sugar”, or “with added iron” all compete for attention. At a glance, it looks like abundance and choice. But look closer: the vast majority of these products are ultra-processed, built from refined grains, fruit concentrates, syrups, and additives — foods designed for convenience, long shelf life, and consistent taste. This wall of packaging is less about nourishing babies and toddlers, and more about reassuring adults who are juggling busy lives, often without the support, time, or resources to prepare whole foods in child-friendly ways.

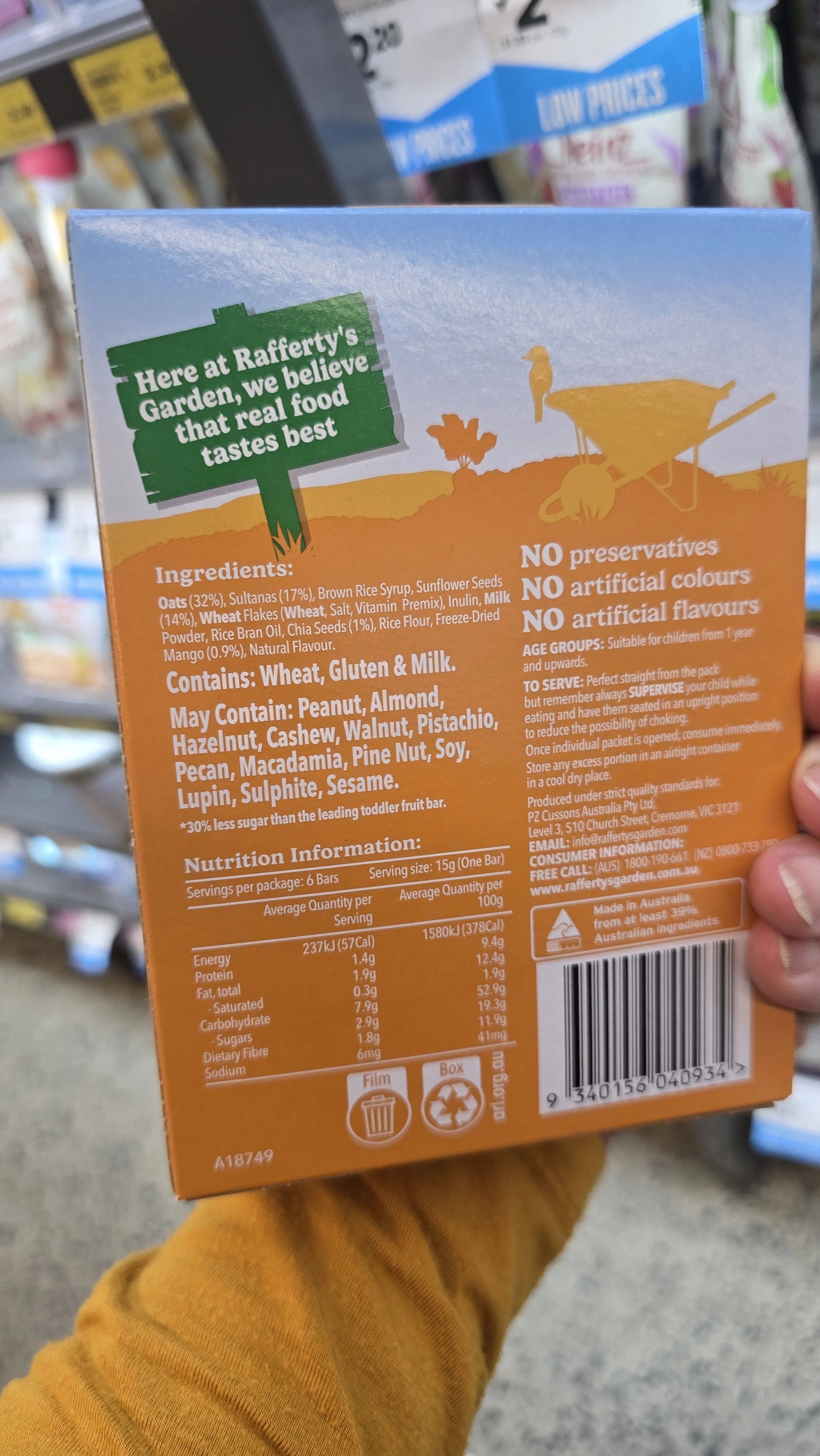

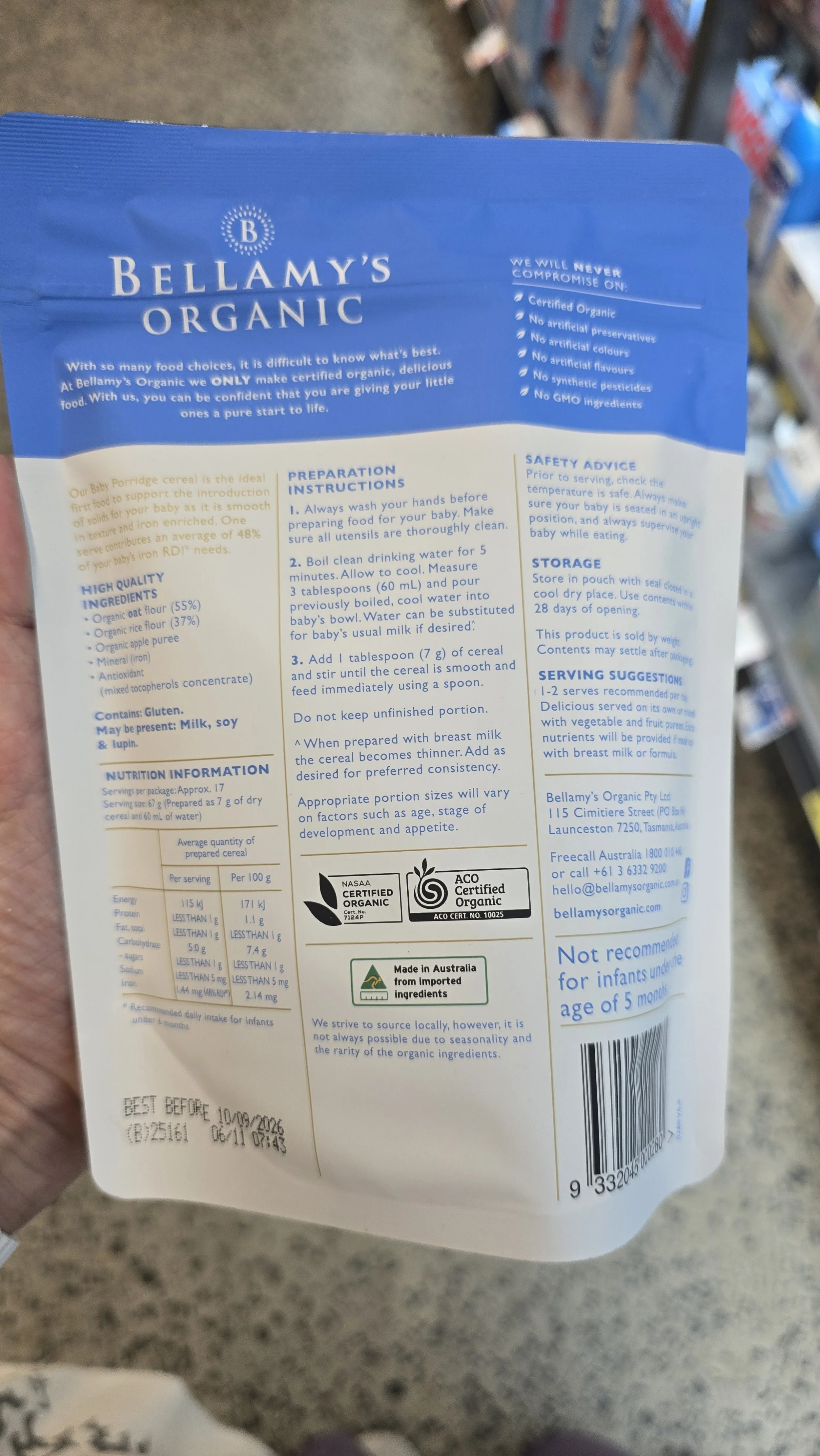

Here is a selection I found at my local supermarket. I included the Tiny Teddies, which I found in the biscuit aisle, for comparison. I finally found that nutrition panel hidden on the bottom of the box!):

How to Read Baby Food Labels

Ultra-processed foods often look healthy on the front of the packet. The truth is on the back. Here are some quick clues:

Front of the pack (marketing):

Bright fruit and vegetable pictures

Buzzwords: organic, no added sugar, fortified with iron, made with real fruit

Smiling cartoon characters or favourite TV icons

Back of the pack (ingredients):

First ingredients matter most. If it starts with rice flour, corn starch, or apple purée concentrate, it’s basically sugar and refined starch.

Fruit concentrates and purées aren’t the same as whole fruit — they’re high in sugars but low in fibre.

Vegetables in trace amounts. If pumpkin, spinach, or carrot appear way down the list, they’re just a token.

Thickeners, gums, or stabilisers keep food smooth and shelf-stable — but they don’t nourish.

Flavourings or “natural flavours” are added to keep kids coming back for more.

A simple rule of thumb: if the ingredients list looks more like a recipe you’d make at home, it’s probably closer to real food. If it reads like a science experiment, it’s ultra-processed.

Scroll to see full table

| Product | Front-of-Pack Promise | What’s Inside | Processing Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arnott’s Tiny Teddy (Chocolate) | “Made with real cocoa”; cute characters; “no artificial colours/flavours/preservatives” | Wheat flour, sugar, vegetable oils, cocoa, milk solids, flavourings | Ultra-processed snack, high in sugar and refined carbs |

| Rafferty’s Garden Mango & Chia Pressed Bars | “30% less sugar”; wholesome fruit and grain imagery | Oats, sultanas, brown rice syrup, sunflower seeds, inulin, milk powder, rice bran oil, chia, rice flour, mango (0.9%) | Processed snack bar with added syrups and powders |

| Rafferty’s Garden Little Smoothies (Coconut Cacao) | “No added sugar”; “with prebiotics”; smoothie-like pouch | Banana puree, pear juice concentrate, apple puree, coconut cream, cacao, linseed, thickeners | Pureed fruit concentrate base, sweet, uniform taste |

| Heinz Little Kids Lentil Puffs (Tomato & Carrot) | “Organic snack”; “with vegetables”; puffed shape for little hands | Lentil flour, maize flour, sunflower oil, powdered veg flavouring | Extruded puff, ultra-processed; tiny % veg powder |

| Only Organic Banana Biscotti | “With added iron”; banana pictures and teddy-bear biscuits | Wheat flour, apple juice concentrate, milk powder, banana puree (4%), raising agents | Sweetened, refined flour biscuit; low banana content |

| Heinz for Baby (Lamb, Veg & Polenta Pouch) | “With Australian lamb”; “no added salt” | Mostly water and veg purée, with 9% lamb and polenta | Highly processed pouch meal; long shelf life |

| Little Bellies Organic Carrot Puffs | “No added sugar”; “source of iron” | Corn flour, sunflower oil, carrot powder, iron fortification | Extruded puff, ultra-processed; minimal carrot |

| Heinz Little Treats Vanilla Custard | “Occasional treat”; “no artificial colours/flavours” | 57% milk, sugar, butter, cornflour, flavouring | Sweet dairy dessert pouch; essentially baby dessert |

| Bellamy’s Organic Baby Porridge | “Good source of iron”; “no added sugar” | Rice flour, pear puree, milk powder, mineral fortification | Refined cereal; fortified but ultra-processed |

| Nestlé Cerelac Baby Rice | “Probiotic”; “source of iron & vitamin C”; teddy bear mascot | 99% rice flour, plus maltodextrin, iron, vitamins, probiotic | Refined instant cereal, heavily marketed by Nestlé |

| Only Organic Pasta Bolognese Pouch | “NZ grass-fed beef”; “organic”; real meal imagery | Water, veg puree, 9% beef, tomato paste, pasta, oil, herbs | Pouch meal; ultra-processed but positioned as home-style |

What’s in the Basket?

Looking across this basket of foods, a pattern becomes clear. Every packet is designed to reassure us — organic, fortified with iron, made with real fruit, no added sugar. And yes, there are nutrients in these products: a little iron here, a little calcium there, some added fibre, even probiotics. But those contributions are scattered, isolated, and often engineered into the product as a selling point, rather than emerging naturally from the food itself.

What stands out most is not the nutrition, but the processing. Almost every product has been stripped down, broken apart, and rebuilt into something smooth, predictable, and easy to swallow. Real fruits and vegetables appear only in powdered or puréed form. Grains are refined into flours, extruded into puffs, or blended into instant cereals. Flavours are carefully controlled so nothing surprises a child’s palate.

Collectively, this basket shows us how baby and toddler foods are marketed less as nourishment, and more as solutions to adult pressures — convenience, safety, reassurance. They fill lunchboxes neatly, they dissolve quickly in the mouth, they promise iron or probiotics or organic purity. But in doing so, they bypass the messy, varied, sometimes challenging experience of learning to eat real food.

That’s the heart of the problem with ultra-processed baby foods. They don’t just replace meals — they reshape expectations. They teach children to prefer bland beige snacks over the unpredictable textures and flavours of whole foods. And they teach parents to trust the packet over their own ability to offer something simple from the family table.

The challenge isn’t to reject every pouch or packet. It’s to recognise them for what they are — convenient fillers, not foundations. Our babies deserve more than a diet of powders, purées and puffs. They deserve real food, shared with family, even if it’s a little messy and imperfect.

Simple Wholefood Snacks That Work

Not every snack has to come from a packet. Here are some simple options:

Fresh and ready: apple slices, mandarin segments, berries, grapes (halved), cucumber or carrot sticks.

Protein boosts: cheese cubes, boiled eggs, chickpeas or beans.

Grains and energy: mini sandwiches, cooked pasta spirals, homemade pikelets.

Little extras: nut or seed butter on fruit, plain yoghurt tubs, leftover roast veggies.

These don’t need to be perfect or fancy. A few simple whole foods go a long way and give children real tastes and textures packets can’t provide.

Beyond the Packaging

Looking down that aisle, it’s easy to see how parents feel reassured by all the bright promises. Labels boast “organic”, “with iron”, “no added sugar”, or “made with real fruit”. The boxes and pouches feature smiling babies, playful animals, and familiar cartoon characters. It feels safe. It feels like the right choice.

But when we flip those packets over, what we find inside tells a different story. Most of these foods are built from refined starches, fruit concentrates, sweeteners, and added thickeners. The tastes are bland and predictable, textures are uniform, and everything is designed to be swallowed quickly and without fuss. For a tired toddler, that’s appealing — and for an exhausted parent, it feels like a win. But over time, these products reinforce a very narrow palate. Children come to expect beige, easy, and always-the-same, while whole fruits, vegetables, and varied textures are rejected as “too much work.”

This is where Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility offers such a helpful reframe. Our job as parents is not to trick, bribe, or endlessly substitute “kid-friendly” versions of food. Our role is to decide what food is offered, when it is offered, and where it is eaten. Our children’s role is to decide whether to eat it, and how much. That means we don’t have to compete with cartoon bears or puffed snacks in a race for what feels easiest. Instead, we can keep returning to simple, nourishing whole foods, offered in developmentally appropriate forms, and trust that children will expand their preferences in their own time.

Of course, that doesn’t mean it’s simple. Whole foods take planning. They need chopping, cooking, and storing. Many parents don’t have the time, energy, or even the kitchen set-up to always prepare “grab-and-go” snacks at home. And in places like daycare, lunchboxes still need to be filled. It’s in these moments that packages leap off the shelf, promising convenience and reassurance in one.

That’s why we need to talk about both sides of this story: the realities of parenting under pressure, and the food industry that’s all too ready to step in with solutions that meet their needs, not our children’s.

The Real Challenge of Whole Foods

Whole foods don’t come in neat packets. They need to be prepared, cooked, or stored. This requires time, energy, skills, and facilities. Meanwhile, packets are instantly ready, reliable, and child-accessible. Supporting parents means sharing low-effort ideas, promoting batch prep, and teaching food skills.

Lunchboxes and Life on the Go

Lunchboxes are another reality. Packaged snacks dominate because they are safe, tidy, and travel well. Fresh foods can bruise, leak, or spoil. Still, balanced alternatives exist: cheese, boiled eggs, fruit, veggie sticks, mini sandwiches, or leftover pasta. These help real foods appear regularly in children’s daily diets.

The Allergy Elephant

Food allergies complicate everything. Excluding staples like dairy, eggs, nuts, or wheat reduces food choices dramatically. Packaged foods with clear allergen labels can feel safer than homemade alternatives. Yet many are ultra-processed. Whenever possible, whole-food swaps like oats instead of wheat, avocado instead of cheese spread, or legume dips instead of nut butter can help.

Influencers and Social Media

Social media restocking videos and “day in the life” clips normalise baby snacks and toddler milks. Influencers weave endorsements into daily routines, blurring lines between life and advertising. Formula and toddler milks appear in this content, skirting WHO Code restrictions.

Parents buy these products because they are marketed as safe and essential. But this isn’t about parental failure. It’s about systemic pressures: maternity leave, lack of support, economic stress, cultural shifts, and relentless marketing.

Division of Responsibility: A Calmer Way to Feed Children

Ellyn Satter’s Division of Responsibility (sDOR) is a simple but powerful model for feeding children without pressure or battles. It gives both parents and children clear roles:

Parents’ job: decide what, when, and where food is offered.

Children’s job: decide whether to eat, and how much.

This framework recognises that children are born with the ability to regulate their own hunger and fullness. Our role is to provide structure, consistency, and a variety of nourishing foods — not to control exactly how much gets eaten.

What this looks like in practice:

You choose and prepare the food, and you set regular mealtimes and snack times.

You sit down together, in as relaxed an environment as possible.

Your child may eat a lot, a little, or nothing at all — and all of those responses are okay.

You don’t bribe, pressure, or coax (“just one more bite,” “eat your veggies first”).

Over time, exposure and trust help children expand their acceptance of whole foods.

Why it matters:

It reduces stress for both parents and children.

It prevents power struggles at the table.

It respects your child’s natural ability to listen to their body.

It helps protect against disordered eating patterns later in life.

In the context of ultra-processed foods, the Division of Responsibility gives us a steady anchor. We can choose to offer more whole foods, knowing that our children may take time to accept them. We can calmly limit packaged snacks without fearing hunger, because we know regular, nourishing food will be offered again soon.

Three Easy Wholefood Snack Recipes

Coconut Banana Muffins (adapted from Live Love Nourish)

Ingredients:

2 ripe bananas,

2 eggs,

½ cup coconut flour,

¼ cup coconut oil,

½ tsp baking soda + lemon juice,

pinch of cinnamon.

Mash bananas, whisk in eggs and oil, stir through dry ingredients, bake at 180°C for 15–20 minutes.

Vegetable Muffin Slice (adapted from Good for Kids, Good for Life)

Ingredients:

1 cup grated zucchini,

1 cup grated carrot,

½ cup corn,

1 cup wholemeal flour,

1 cup grated cheese,

3 eggs,

½ cup milk,

2 tbsp olive oil.

Method: Mix veggies, flour, cheese. Whisk eggs, milk, oil. Combine, pour into tin, bake at 180°C for 25–30 minutes.

Strawberry Ice Blocks (adapted from Raising Children Network)

Ingredients:

2 cups strawberries,

1 cup plain yoghurt,

1 tbsp honey (optional, not for under 1s).

Method: Blend, pour into moulds, freeze for 4+ hours.

Closing Thoughts

This isn’t about guilt or perfection. It’s about awareness. By recognising how much of our babies’ diets are shaped by industry, we can take small steps toward balance. Every apple slice, every piece of cheese, every veggie stick or homemade muffin counts. Awareness, small steps, and shared responsibility — that’s how we move beyond ultraprocessed babies.

Further Reading:

Ultra-Processed People: Why We Can't Stop Eating Food That Isn't Food Chris van Tulleken

The Gentle Eating Book Sarah Ockwell-Smith

Inventing Baby Food Amy Bentley