Witness and Legacy: The Photographers Who Traveled the World to Document Traditional Cultures

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the world was changing at a breathtaking pace. Empires expanded, railways carved through forests and plains, and new technologies — like photography — allowed people to see distant lands and cultures for the first time. In this moment of intense curiosity and colonial expansion, a generation of photographers set out to "document" Indigenous and traditional peoples around the world.

Armed with bulky cameras and heavy glass plates, these photographers traveled by ship, horse, camel, canoe, and on foot to some of the most remote corners of the earth. They captured images of Sámi reindeer herders in Scandinavia, Ainu families in Japan, Himba mothers in Namibia, Dyak communities in Borneo, Mapuche families in Chile, and countless other groups from every inhabited continent.

A glimpse into the early days of photography — and the dedicated work behind so many of the historical images we now treasure.

This portrait shows a professional photographer standing proudly among his large-format cameras, likely in the late 19th or early 20th century. Each camera required careful setup, long exposures, and glass plate negatives — a far cry from the instant snaps of today.

These early photographers played a vital role in documenting everyday life, cultural practices, and family moments across the globe. Their work helped preserve glimpses of traditional babywearing and caregiving practices that may otherwise have been forgotten.

Before baby carriers were mass-produced, before parenting content went viral, it was the steady hands of photographers like this — patient, precise, and deeply curious — who gave us the earliest visual records of how we carried our children.

A mindset of urgency — and misunderstanding

These photographers often believed they were preserving the "last glimpses" of cultures they thought were destined to vanish under the pressures of modernization and Western expansion. This idea — known as "salvage ethnography" — was shaped by a colonial mindset that saw non-Western ways of life as static and inevitably doomed.

While their work preserved remarkable details of clothing, jewelry, tools, rituals, and daily life, it also reinforced harmful stereotypes. Many subjects were posed in ways that emphasized "exotic" qualities for curious audiences back home. Sometimes people were asked to wear outdated garments, stage scenes that did not represent contemporary realities, or present themselves as "types" rather than individuals.

The double-edged legacy

Today, these images can be seen as both deeply problematic and profoundly valuable.

On one hand, they were often created without consent and stripped context from the people and practices they depicted. They reduced vibrant, living cultures to museum pieces, reinforcing ideas of Western superiority and "progress."

On the other hand, these photographs have become irreplaceable records. In many cases, they are the only surviving visual evidence of certain hairstyles, tattoo patterns, woven textiles, or baby-carrying methods. Descendants today use these images to revive traditional techniques, restore cultural pride, and reconnect with ancestors in powerful ways.

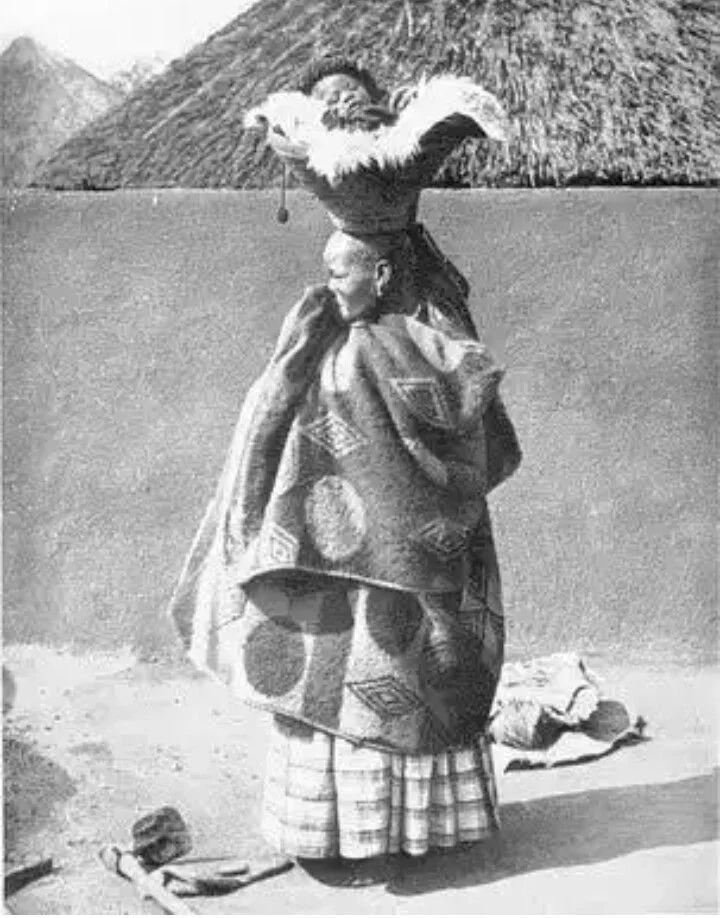

In this historical photograph, a Basotho woman from Lesotho carries her baby in a unique and beautifully practical style. Instead of being worn on the back or front, the baby is carefully nestled in a large, padded hat or basket balanced on the mother’s head — a method sometimes used for very young infants during short, local trips.

The mother is wrapped in the iconic Basotho blanket, known for its bold geometric patterns and deep cultural significance. These blankets are treasured items that symbolize warmth, protection, and identity, and they play a central role in Basotho life from birth through to ceremonial occasions.

Her strong, upright posture and composed expression convey a quiet pride and resilience. This image highlights not only the resourcefulness and adaptability of mothers across cultures but also the deep integration of traditional textiles and carrying methods into daily life. It’s a powerful testament to the many ways communities have innovated to keep their babies close, safe, and nurtured while fully engaged in the flow of work and movement.

Babywearing as a global thread

For those of us passionate about babywearing traditions, these photos hold particular magic. Across the world, babies have been carried in woven shawls, bark cloth slings, fur-lined cradles, knotted scarves, rigid back baskets, and ingeniously designed wraps.

We see Quechua mothers in the Andes using colorful mantas to keep little ones close as they walk steep mountain paths. We see Korean women using the podaegi wrap, carefully binding babies snug against their backs. We see Nigerian women with richly patterned wrappers tied expertly around their torsos, balancing heavy market baskets in one hand and a sleeping baby in the other.

In each of these, the carrier is not merely a tool — it is an expression of love, skill, and cultural identity. These images show us babies kept safe and warm, soothed by a parent’s heartbeat, and included in every aspect of daily life.

In this striking historical photograph, an Irish mother stands proudly outside her stone cottage, carrying heavy milk pails and her baby at the same time. Her traditional dress and patterned headscarf speak to rural Irish life in the late 19th or early 20th century, a life of hard work and close family bonds.

The baby is snugly secured on her back using what appears to be a simple woollen shawl or large cloth — a style widely used in Ireland and across the British Isles. This improvisational carrying method shows the practical and resourceful spirit of mothers who needed to keep little ones close while tending to essential tasks.

Beside her stands her older child, barefoot and smiling shyly, embodying the warmth and resilience of rural Irish families. Together, they reflect the timeless story of mothers everywhere: weaving care and labour into one continuous rhythm, strengthened by love and community.

Modern colorists: Bridging past and present

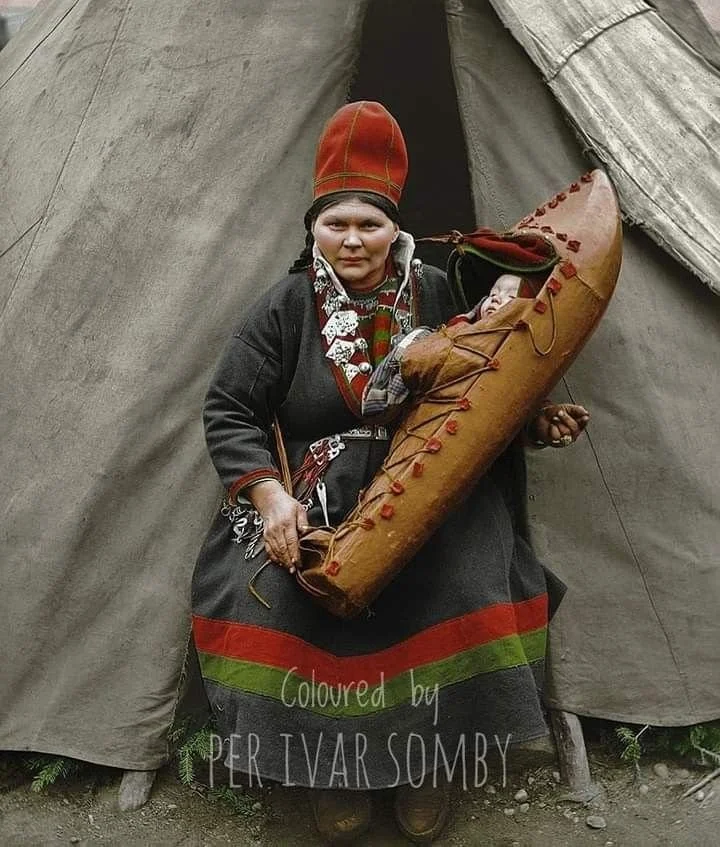

In recent years, a new generation of digital colorists has begun breathing new life into these black-and-white images. By adding subtle skin tones, recreating textile colors, and highlighting the vibrancy of traditional adornments, they make these historical portraits feel immediate and relatable to modern viewers.

When done with sensitivity and deep respect for the people depicted, colorizing can offer fresh ways for descendant communities to engage with these archives, sparking renewed interest in family stories, clothing patterns, and craft techniques.

However, this practice is not without ethical complexities. Some colorists and commercial agencies now sell usage rights to these images — including prints, NFTs, or branded content — without engaging with or compensating the communities whose ancestors appear in them. This can be seen as a continuation of exploitation, turning deeply personal cultural heritage into marketable products for profit.

As with the original photographers, we must ask: Who benefits? Who decides how these images are used? And how can we ensure that descendants have a voice — and ideally, ownership — in how their ancestors are represented and shared?

This colourised historical photograph, brought to life by Per Ivar Somby, shows a Sámi woman standing outside a lávvu with her baby in a traditional cradleboard known as a komsekule.

Carved from wood and wrapped in richly detailed leather, these cradleboards kept Sámi babies safe, warm, and close — whether resting indoors, travelling by sled, or carried on foot. The intricate lacing and embroidery reflect both practicality and deep cultural meaning, passed through generations of Arctic caregivers.

This is not only a portrait of a mother and child — it is a living thread of Sámi heritage, cradled in strength, connection, and care.

Moving forward with respect

As we engage with these images today, we must acknowledge their complicated origins. We can honor the photographers' technical skill and dedication while recognizing the colonial power dynamics and sometimes exploitative framing.

Most importantly, we center the people in the images — their resilience, creativity, and enduring presence. These communities did not disappear. Despite immense pressures, many have maintained and revitalized their languages, ceremonies, crafts, and child-rearing practices.

What those early photographers saw as a "last glimpse" has turned out to be a thread of continuity, woven anew by each generation.

21st Century

Today a different group of people travel the world, cameras in hand. Tourists today can visit literally every nook and cranny of planet earth.

“Take only photos, leave only footprints”

Communities who once lived parallel to western cultures now rely on their tourists for income. And they will often dress up in traditional costumes and baby carriers to be photographered - for a fee. Once again, we might be viewing staged photos which don't necessarily portray actual everyday life.

Final thoughts

Photography is powerful. It can freeze moments in time, carry memory across oceans and centuries, and — when wielded unethically — distort and exploit. But it can also become a bridge, reconnecting descendants to ancestors and helping to repair ruptured histories.

As we study these images today, let’s look with both critical eyes and open hearts. Let’s recognize both the harm and the heritage — and help carry forward the stories they hold, with deep respect for the living cultures they represent.