The Heartbeat of the Village: The Importance of Babywearing for the Whole Community

In traditional societies around the world, the success and survival of the community have always depended on cooperative care. At the center of this woven support network is the simple, powerful act of carrying babies. Babywearing is far more than a method of transport — it is a living expression of shared responsibility, collective love, and the deep understanding that children belong not only to their parents but to everyone.

Everyone carries.

Elders cradle babies on their backs or hips as they move slowly through the village, sharing stories, humming ancestral songs, and teaching through gentle presence. In the Congo Basin, among the Mbendjele and BaYaka forest communities, elders and even older siblings take turns carrying infants in bark cloth wraps or simple woven straps, ensuring constant closeness and care. Children learn forest sounds, plant lore, and social cues while resting against the heartbeat of an elder.

Older children step naturally into caregiving roles. In rural Mexico, older sisters often carry babies in rebozos — woven shawls used to wrap the baby securely against their small backs or hips. In West African communities, older siblings proudly carry the little ones in colorful kanga or lappa cloths, a practice that fosters patience and a strong sense of family connection from an early age. This shared responsibility is not a chore but a joyful introduction to the cycle of nurturing and belonging.

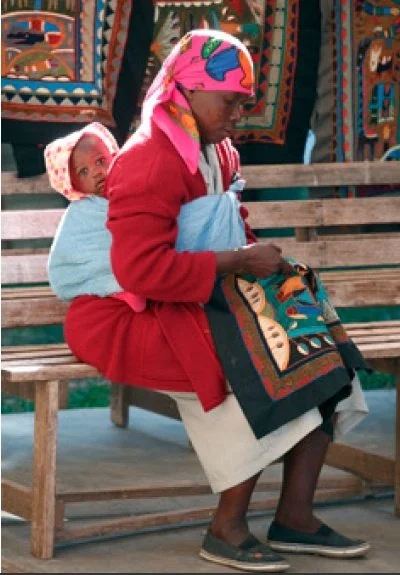

Women, often the primary gatherers and providers, keep their babies close as they work. In the Andes, Quechua and Aymara women wrap their babies in mantas, brightly colored cloths tied high on their backs. As they climb steep terraces or weave in communal courtyards, the baby shares in the mother’s warmth, scent, and daily sounds. In Mongolia, mothers swaddle their babies tightly in quilted wraps or place them in wooden cradles that can be carried or swung from saddles, ensuring the child remains part of nomadic life.

In the Arctic, Inuit mothers carry their babies inside the large hoods (amauti) of their parkas. The baby is kept close to the mother's body for warmth and protection from icy winds, listening to her heartbeat and sharing her breath in the harshest of climates. In the deserts of North Africa, Bedouin women use shoulder cradles or simple cloth wraps to carry infants while they walk long distances in search of water or tend herds.

Carrying keeps babies safe and included.

A baby on a mother’s back is far from danger — away from sharp tools, cooking fires, or the rush of animals. The soft sway of each step, the heartbeat beneath their ear, and the mother’s voice above become the baby’s first lessons in trust, rhythm, and language. This closeness shapes the foundation for secure attachment and lifelong social bonds.

In the Philippines, Tagalog and Visayan women use an alampay or woven carrier, securing babies at the hip or back while harvesting rice or weaving mats. In parts of India, rural women use long saris or cloths tied diagonally across the chest, keeping the baby snug while carrying water pots or working in the fields.

Among the Maasai of East Africa, mothers and grandmothers use animal skin wraps or colorful kangas to hold their infants close as they herd cattle or gather firewood. In Papua New Guinea, mothers use string bags (bilum) slung across the forehead or shoulders, carrying babies as they navigate forest paths or attend market days.

Across these diverse landscapes — from icy tundras to dense rainforests, from mountain terraces to bustling market towns — the method of carrying might differ, but the message is the same: a baby belongs within the heart of daily life, not separated from it.

This practice is not only about practicality but about weaving the child into the fabric of community from the very start. The baby is exposed to language, to work rhythms, to laughter and song, to the wisdom of elders and the chatter of siblings. They learn, quite literally, from being carried through the world.

This system of cooperative care strengthens social bonds and ensures the survival of both individuals and the collective. Children raised in this way grow up understanding that they are never alone — they are part of a wider circle of arms ready to lift them up.

In a world that often celebrates independence and isolates parents into nuclear units, these traditions remind us that caregiving is meant to be shared. They teach us that parenting is not a solitary task but a community dance; that each elder’s hand, each sibling’s giggle, each mother’s step is part of a living embrace.

In every knot tied, in every quiet lullaby, in every gentle sway across fields or forest paths, there is a clear, timeless message echoing across generations:

You belong. You are loved. We carry you together.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.