Central Asia, Mongolia & the Caucasus: Steppes, Sashes, and Cradle Songs

Across the Steppe and Saddle: Babywearing in Central Asia, Mongolia & the Caucasus

Across the vast grasslands and rugged mountains of Central Asia, Mongolia, and the Caucasus, the rhythms of nomadic life have shaped parenting practices for centuries. In these cultures, families have long relied on practical solutions to keep their youngest members safe and calm while tending herds, moving camp, or weaving textiles in felt-lined yurts and stone houses.

While cradles such as the beshik, urkh, and cradle boards are central to daily life, body carriers are also part of the cultural fabric—especially among nomadic Turkic and Mongolic peoples. Simple sashes, wraps, and shawls allow mothers to carry babies on the hip or back for short periods, particularly during chores or travel. These textiles, often repurposed from clothing or woven with intention, reflect the artistry and practicality of communities shaped by mobility and resilience.

In Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, colorful woven cloths sometimes support a baby on the hip or back during household tasks or walks between camps. In Mongolia, soft woollen sashes hold infants against a mother’s back while she milks the animals or prepares food. In the Caucasus, mountain-dwelling communities occasionally wrap swaddled babies in large shawls for transport or shared gatherings.

These wraps are more than functional tools; they carry the scent of yurts and mountain air, the hum of lullabies, and the stories of generations. Babies learn the sway of the saddle and the rhythm of footsteps from the warmth of their mother’s back.

Among these, a remarkable example of a traditional baby carrier comes from the Shavak tribe of eastern Anatolia. Though geographically closer to Western Asia, their cultural and weaving traditions overlap with those of Central Asian nomadic peoples. The ‘turik’ baby carrier from the Tunceli region, under the Munzur mountains, is crafted using the fine soumac weaving technique. The front features high-quality, tightly spun wool in vibrant natural dyes—intense cochineal reds, deep indigo blues—while the back is finished in flatweave kilim. White triangular bands are formed from fine cotton, adding both structure and meaning. Woven in two panels on a narrow loom, the piece is distinct from other triangular baby carriers found in Van and Hakkari, known as ‘parzun.’

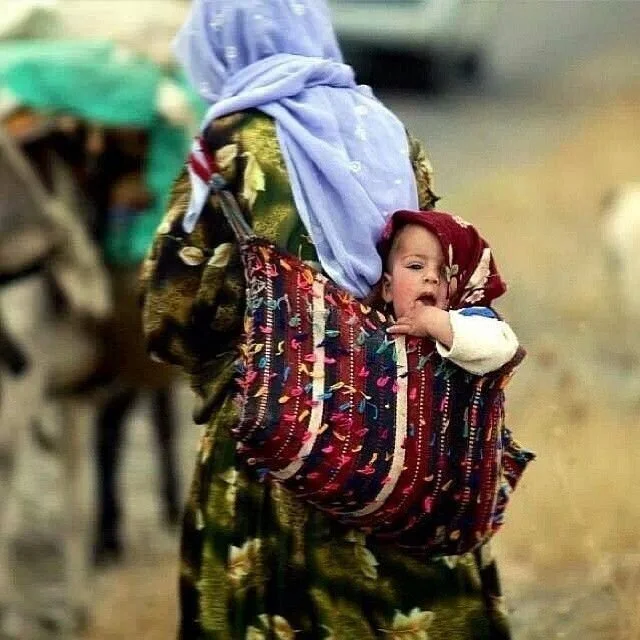

This captivating image shows a baby nestled in a richly patterned woven cradle bag, suspended from their mother’s shoulders as she walks a dusty path. The woman’s floral robe and lavender headscarf suggest she may belong to a Kurdish or Iranian pastoral community. The carrier—a vibrant, handcrafted textile with vertical stripes and stylised motifs—is both a cradle and a sling, perfectly suited to a mobile way of life. The baby’s little hand peeks over the edge, eyes wide open to the world around them. It’s a beautiful reminder that in many cultures, mobility and nurture are woven into daily life—both literally and figuratively.

This striking photograph shows a Kurdish mother tending to her infant while seated in the open grasslands, surrounded by a flock of sheep — a glimpse into the semi-nomadic pastoral life still lived by many in Eastern Turkey, Northern Iraq, or Western Iran.

The baby rests snugly inside a vividly striped woven cradle bag, likely handmade and richly textured, its seams reinforced with colourful stitching. This style of baby carrier — often used by Kurdish and other regional nomadic groups — allows infants to remain warm, secure, and close while their mothers move between work and rest.

The mother’s layered clothing, patterned headscarf, and gentle expression speak of deep care rooted in tradition. Her practical posture and surroundings reflect a way of life in which mothering and labour are seamlessly interwoven — feeding a child and tending livestock, all in the same rhythm of the day

It is an image full of colour, quiet strength, and cultural continuity — a reminder of how place, identity, and parenting are beautifully entwined.

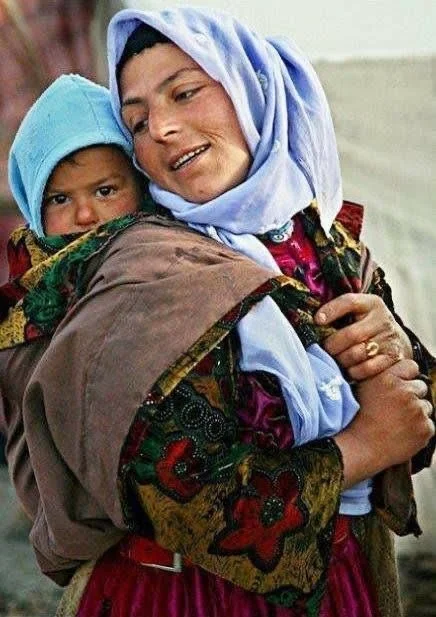

In this tender moment captured high in the mountains, a Kurdish mother cradles a newborn lamb while her own baby rides safely on her back in a richly patterned woven carrier. The cloth is likely handmade — a traditional Kurdish or Luri textile, repurposed with care to keep her little one close as she works.

Her baby is snuggled securely in a wide fabric pouch slung across her back, arms free and head supported — a practical, time-honoured way of babywearing that allows mothers to remain connected with their children while tending to animals or daily tasks. These carriers are often woven by hand using wool or goat hair, with patterns passed down through generations.

Her layered clothing, including the white headscarf and woollen overcoat, is typical of Kurdish women in pastoral regions of Iran, Iraq, Turkey, or Syria. Every detail — from the baby’s position to the affectionate exchange with the lamb — speaks of a life rooted in land, family, and care.

In this serene rural scene, a Kurdish mother carries her sleeping baby snugly in a boldly striped woven cradle bag, slung over one shoulder and resting against her hip and back. The thick, sturdy fabric—vibrant in reds, blues, and yellows—cradles the baby in a deep hammock-style seat, layered with warm blankets. Her traditional clothing, including a dark headscarf dotted with tiny florals and a sheer embroidered top, reflects the heritage of Kurdish communities in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran. This style of babywearing remains deeply rooted in nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralist traditions of the region, offering comfort, security, and mobility for both mother and child.

These heirloom textiles are not only designed for carrying but also embody spiritual and familial meaning. Patterns may reflect protective symbols, tribal identity, or maternal blessings. Today, such carriers are preserved in collections and remembered through the images captured by photographers like Josephine Powell, whose work honours vanishing nomadic lifeways.

Carrying Traditions and Textiles

In this evocative photo, a woman milks a goat amid a mountain pasture, smiling as she works with her baby securely wrapped on her back. The child is tucked into a warm layered bundle, peeking curiously over her shoulder. This scene likely depicts a pastoral nomadic family from the Zagros or Alborz mountain regions of Iran, or possibly eastern Turkey. The traditional layered wrapping and woolen outerwear reflect the cool climate, while the mountainous backdrop and the presence of the herd suggest a transhumant lifestyle—moving seasonally with livestock. As she works, the baby remains close, comforted by her rhythm and warmth, part of daily life from the very beginning.

At a bustling outdoor gathering—likely a local market or cultural festival—this Turkish mother carries her baby high on her back in a richly adorned woven cloth. The wrap is trimmed with vibrant tassels in jewel tones, echoing the decorative flair of her traditional headdress. Her pink sweater adds a modern splash of colour, blending past and present. The baby, dressed in soft cream and denim, peers out with a solemn, observant gaze, held securely in a deep seat formed by the simple yet effective wrapping method. This style of babywearing is typical in Anatolian and Kurdish regions of Turkey, where colour, craft, and close connection go hand in hand.

Among many Turkic and Mongolic nomadic groups, soft cloth wraps and sashes have long been used to secure babies to the mother’s or caregiver’s back or hip. These wraps, often repurposed from everyday garments or specially woven sashes, allow caregivers to ride horses, herd animals, and tend to camp chores while keeping babies close and safe. Babies learn the sway of the saddle, the sounds of flutes and throat songs, and the scent of felt yurts from the warmth of their mother’s back.

Wrapped close in a cascade of floral fabrics and earthy tones, this mother carries her child in a traditional style common across rural Afghanistan and neighbouring Central Asian regions. Her layers—practical yet vibrant—reflect both protection from the elements and deep cultural heritage. The baby is tucked in behind her, peering out from a hooded cap with a steady, thoughtful gaze. Though the wrap is simple—a series of garments layered and tied—it holds the child securely and intimately against her back, hands free for the work of daily life. There’s quiet strength in her posture and softness in her smile: a moment of connection, caught in motion.

In the Caucasus, especially among mountain-dwelling communities, traditional shawls and large woven cloths are tied securely to support infants while climbing steep paths and working in terraced fields. Decorative sashes and embroidered elements may symbolize family lineage or offer protective blessings, echoing the deep importance of textile art throughout the region.

Textiles in these regions carry immense cultural weight: colors and motifs often indicate tribal affiliation, marital status, or local legends. The act of weaving and wrapping is seen not just as a necessity but as an art form and a spiritual practice, each knot a silent prayer for the child’s safety and strength.

Modern pressures — including sedentarisation policies, urban migration, and Western influences — have shifted some carrying traditions. Yet many families, particularly in rural areas, continue to teach these skills as a vital thread of cultural continuity and pride.

To be carried across the steppes or mountain paths of Central Asia and the Caucasus is to be introduced to the wide sky, the echo of drumbeats and horse hooves, and the stories of ancestors whispered into mountain winds. It is to be cradled in a song that celebrates freedom, belonging, and the enduring spirit of nomadic life.

"This image captures the remarkable strength and resilience of pastoral mothers in the Caucasus region. Wrapped snugly in a patterned shawl, the child rides safely on the mother’s back as she carries two young lambs through a snowy forest. Such traditional wrapping techniques allow mothers to keep children close and warm while continuing essential daily work — a practice deeply rooted in the rhythms of family and land."

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.