Carriers as Art: Materials, Craft, and Heritage

Baby carriers have always been more than simple tools — they are works of art, living expressions of the places and people who create them. Across the world, caregivers have drawn on local materials and traditional techniques to craft carriers that are both practical and profoundly beautiful.

In tropical regions, strong yet breathable fibers are favored. In the Pacific Islands, pandanus leaves and coconut fibers are woven into intricate slings and wraps that keep babies cool while allowing air to circulate. In Papua New Guinea, bilum bags are made from plant fibers knotted into an open, net-like weave, which stretches and cradles the baby gently.

Pandanus Weaving

In this striking image, a woman from Papua New Guinea carries her baby in a traditional bilum — a handwoven net bag made from plant fibres. Slung over her head with a tumpline and resting across her back, the bilum cradles her baby close in a deeply rooted form of care and transport. This style of carrying is common across the highlands and lowlands of Papua New Guinea, where the bilum is an essential item used for everything from produce to children. Her red skirt and shaved head reflect customary practices in many village communities.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, the selendang — a long rectangular cloth — is used daily as a baby carrier, head covering, or shawl. Soft and versatile, the selendang is often woven or dyed with beautiful motifs that reflect regional identity, stories, and spirituality. Using a selendang to carry a baby is an intimate act, blending warmth, artistry, and adaptability.

Seleandang Fabrix

Indonesia is also famous for its batik textiles — painstakingly dyed using wax-resist techniques. Each motif carries meaning, representing protection, prosperity, or connection to the natural world. Bark cloth in parts of eastern Indonesia and the Pacific reflects deep knowledge of local plants and traditional cloth-making skills.

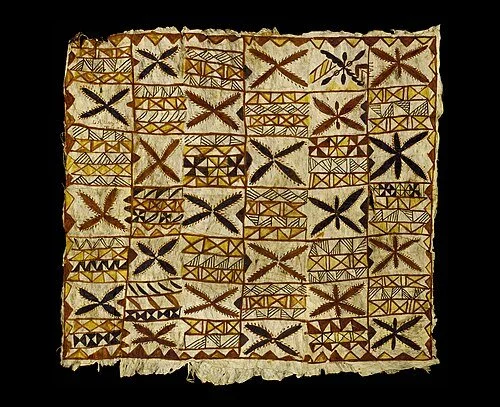

Batik Design

On the ancient stone terraces of Borobudur in Central Java, a father carries his child close in a traditional selendang, or batik cloth. The rich brown and cream pattern of the fabric is wrapped snugly across his shoulder and around the child, securing her on his hip with practiced ease. This everyday gesture of care and connection is rooted in centuries of tradition — the selendang serving as both a carrier and a cultural symbol, passed down through generations. His steady presence and the child’s alert gaze reflect the quiet strength of familial bonds woven into daily life across Indonesia.

In Africa, bold printed cotton cloths such as khanga, kitenge, and capulana are commonly used to secure babies on the caregiver’s back. Beyond their striking colors and patterns, these textiles often carry proverbs and blessings, turning each wrap into a moving tapestry of cultural pride and wisdom. These “wax print” techniques were brought to Africa from Indonesia by Dutch merchants in the 19th century and soon become popular for their vibrant colours and patterns.

African Wax Print Fabric

Two mothers sit side by side in a health clinic in Zimbabwe, their babies contentedly sleeping on their chests, snug in vivid chitenges — traditional rectangular cloths used for carrying. The cloths are expertly tied over one shoulder and around the torso, creating a secure pouch that keeps the babies upright and close. This simple, deeply rooted practice provides warmth, bonding, and ease during long waits or daily tasks. The bright, bold patterns speak of pride, resilience, and everyday motherhood — the universal rhythm of caring, waiting, and carrying.

In the Andes, aguayos — brightly colored woven cloths — blend complex geometric patterns with spiritual and communal meanings. These cloths are not only used to carry children but also to transport food, firewood, or market goods, underscoring their integral role in daily life.

In the highlands of Peru, a circle of Quechua women weaves together — not just yarn, but tradition, community, and identity. Each woman is tethered to a backstrap loom anchored at the center, their vibrant skirts and red montera hats forming a striking contrast to the earth beneath them. The backstrap looms stretch out like spokes of a wheel, binding them to shared rhythm and skill. These textiles — rich with symbolic colour and pattern — are the same cloths that wrap their babies, carry food, and express belonging. Weaving here is generational work, carried forward with quiet focus and strong hands.

Outside an adobe-walled home in the highlands of Peru, three Quechua women sit together in a shared rhythm of craft and colour. One works at a backstrap loom stretched between a post and her waist, weaving radiant stripes of magenta, orange, red, and turquoise. The others sit beside her, hands busy with yarn, their skirts bright and layered, jackets richly embroidered, and bowler hats worn with pride. Bundles of wool in every shade spill across the ground, ready to be spun into the stories of their ancestors. Here, weaving is not only tradition — it is community, identity, and connection woven into every thread.

Aguayo fabric

This richly detailed image captures the hands of a Maya woman from Guatemala as she weaves vibrant floral patterns into cloth using a traditional backstrap loom. Her fingers move with practiced precision, guiding the threads to life. The loom is anchored around her back and fixed to a stable point ahead, allowing her body to maintain the tension — a technique passed down through generations. The colourful textile in progress reflects not only skill, but identity and culture. These weavings often become rebozos, carrying cloths, or traditional garments, embodying deep meaning and connection to both ancestry and everyday life.

A baby peeks out from a vibrant rebozo wrap, carried high on the back of a caregiver in Guatemala, part of the Mesoamerican region. The baby’s colourful crocheted hat, adorned with bright geometric patterns and a pom-pom, echoes the dazzling hues of the woven textile — likely a traditional tzute or perraje. These handwoven cloths are deeply significant in Indigenous Maya culture, used for everything from babywearing to ceremonial dress. The fabric is tucked securely across the caregiver’s chest and shoulder, holding the baby close in a time-honoured position. This image radiates warmth, continuity, and cultural pride, carried in cloth and connection.

In East Asia, embroidered panels on podaegi in Korea and meh dai in Cantonese communities are adorned with floral and symbolic motifs, each stitch offering prayers and wishes for health, happiness, and good fortune. Even the simpler Japanese onbuhimo showcases careful textile choice, reflecting aesthetic traditions and cultural values.

Chinese Embroidered Fabric

This close-up image captures the vibrant detail of hand-embroidered textile panels traditionally used in Hmong clothing. Arranged in orderly rows, each square features an intricate, symmetrical motif—bold crosses, florals, and spirals—stitched in striking combinations of fuchsia, turquoise, orange, purple, and green. The designs are bordered by bright neon sashing, and some panels are finished with thick fringes in rich red, green, and deep indigo. These embroidered pieces are not only decorative but deeply cultural—communicating identity, clan affiliation, and heritage through colour and pattern.

A Flower Hmong mother walks through the marketplace with her baby securely carried on her back in a vibrantly embroidered traditional carrier. Her woven textile wrap is richly adorned with intricate beadwork, bright threads, and geometric floral motifs, showcasing the extraordinary skill of Hmong artisans. The baby peeks out from a warm, layered bundle of fleece and knitted wool, protected by the structured fabric panel and wide shoulder ties. The woman’s jacket and headscarf echo the same colourful aesthetic—striped sleeves, ornate fringe, and bold reds, blues, and yellows that reflect both cultural pride and personal flair.

📷 Photographed in Bac Ha, northern Vietnam.

In colder climates, warmth shapes design above all else. Among the Sámi, cradleboards are lined with soft reindeer hides and moss to protect babies from Arctic cold. In southern Australia, possum skin cloaks provide warmth and security, with each cloak carefully incised to tell family stories and connect the wearer to Country and kin.

sami komse

A Sámi mother in traditional gákti dress cradles her baby in a beautifully crafted komse — a Sámi cradleboard used by Indigenous communities across Sápmi, which spans parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. The cradle is richly adorned with handwoven bands, tassels, and a curved wooden hood, designed to protect the baby from harsh Arctic winds. Often lined with reindeer fur and wrapped in soft textiles, the komse allows the baby to be carried, rocked, or secured on a sled or reindeer. This enduring design reflects both practicality and deep cultural care in Northern Europe’s Sámi communities.

Inuit amauti

An Inuit mother carries her child close in the warmth of a traditional amauti, a parka uniquely designed with an extended back pouch for safely holding babies. Made from thick fur and expertly tailored for Arctic conditions, the amauti offers protection from extreme cold while keeping the child snug against the mother’s back. The child’s head peeks out from the soft fur-lined hood, framed by the luxurious textures of sealskin or caribou hide. This timeless design allows for closeness, mobility, and comfort, sustaining deep cultural roots and generations of knowledge passed down through mothers and grandmothers.

Possum Skin cloak

With careful strokes and cultural pride, an Aboriginal woman paints a possum skin cloak alongside a young child, sharing not only her knowledge but her connection to Country and kin. The intricate designs tell stories — of land, lineage, and belonging — passed through generations in ochre, linework, and warmth. Cloaks like this one are more than garments: they are maps, memory, and identity. As the child leans close, watching the brush move across fur, we glimpse the quiet power of cultural continuity and the importance of passing traditions hand to hand, heart to heart.

In this tender moment, a newborn baby lies nestled against their mother’s chest, wrapped in a traditional possum skin cloak — yapa — offering warmth, comfort, and cultural connection from the very first hours of life. Among many Aboriginal communities of south-eastern Australia, these cloaks are not only practical garments but carry deep spiritual and ancestral significance. They are used in ceremonies, healing, and as a way of honouring Country and kin. Possum skin cloaks are often etched with markings representing the child's family, land, and journey — a way of holding stories close.

Wrapped in a rich red cloth and nestled against a possum skin cloak, this newborn rests peacefully in a coolamon — a traditional wooden carrying vessel. A soft white ochre line on the baby’s forehead marks this moment with cultural meaning and belonging. In Aboriginal communities across Australia, the coolamon has long served many purposes: cradling babies, carrying food, and holding stories. The use of ochre and possum skin connects this child to land, kin, and Country, wrapping them not just in warmth, but in identity and tradition from their very first days.

Every material — from the softest wool to woven bark or cotton — is chosen with deep care, rooted in intimate knowledge of the land and a profound sense of what it means to nurture. The craft of each carrier becomes a living language: a way to speak love, share history, and pass wisdom from one generation to the next.

For many families, a carrier is an heirloom, gaining layers of meaning as it embraces each new baby. These carriers are not merely functional items — they are living archives of community memory, resilience, and continuity.

In today’s world of mass production and disposable goods, handmade carriers stand as quiet declarations of connection: to craft, to land, to each other. Wrapping a baby in cloth that carries ancestral stories and the spirit of community is a powerful reminder that art lives not only in galleries but in the tender, everyday acts of love that hold us together.

Further reading:

The Inuit Art of Baby-Carrying Using the Amauti

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.