British Isles: Shawls, Songs, and Silent Threads

Gwisgiadaw Cymreig – Mode of Carying infants’ One of a set of 16 numbered prints dated 1.5.1853.

In the misty landscapes of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and the broader British Isles, babywearing traditions echo ancient rhythms of hearth and field. Though often overshadowed by later industrial shifts, these practices reflect deep ties to family, land, and shared community life.

Wales

In Wales, the Welsh nursing shawl stands out as a beautiful example of practical and cultural weaving. Traditionally made from wool, these large shawls were used to carry babies on the hip or back while mothers worked in the fields or around the home. Babies snuggled against the warmth of the wool, listening to the lilting cadences of song and story in Cymraeg (Welsh language), feeling the movements of daily life woven through each wrap and knot.

A Welsh woman stands proudly, her baby wrapped snugly in a large fringed shawl, held high and close in the classic front carry known throughout Wales. The baby rests upright against her chest, swaddled in soft cloth and crowned with a lace bonnet, eyes just barely peeking from the folds. The wrap crosses over one shoulder and around the waist — a method handed down through generations, practical and instinctive, rooted in everyday care.

She wears the unmistakable tall Welsh hat, adding a sense of cultural pride to this quiet portrait of mothering. Her expression is calm, even dignified, and her stance sure — as if to say, this is who we are: mothers who carry, women who hold tradition close while raising the next generation within it.

This is babywearing as heritage — not a borrowed technique, but a native one. The shawl isn’t just an accessory; it is a carrier, a garment, a shelter, and a symbol. Worn with confidence, tied with purpose, and woven through with story.

This lively 1940s street scene from Wales beautifully captures a moment of community among mothers. The woman in the center wears a traditional Welsh shawl, skillfully wrapped to carry her baby snug against her chest. These checked wool shawls were an everyday essential for Welsh women, not just for warmth but as practical baby carriers, showcasing a long-standing tradition of keeping babies close. The fringed edges and heavy woven fabric highlight local textile heritage. While the other mothers hold their babies in arms, the shawl shows a hands-free option already deeply rooted in everyday life. This image celebrates the blend of culture, craft, and connection between mother and child.

In this intimate and tender photograph, we see a Welsh mother holding her baby snugly wrapped in a traditional nursing shawl. The checked woolen shawl, known in Wales as a siol fagu, is wrapped securely around the baby and tied around the mother’s waist, allowing her to support and carry her child close to her body.

The mother’s soft expression, as she looks lovingly at her baby, radiates warmth and devotion. The baby, wrapped in layers and topped with a delicate bonnet, looks peaceful and safe in the embrace of the shawl — and the secure arms of the mother.

This style of shawl carrying was common in 19th- and early 20th-century Wales, particularly among working women who needed to keep their little ones close while continuing their daily tasks. The image beautifully embodies the timeless instinct to keep children warm, protected, and comforted, using simple yet ingenious traditional textiles passed down through generations.

A mother stands calmly, gazing directly at the camera, her child wrapped securely at her front in a fringed woolen shawl. The wrap crosses her shoulder and loops wide around the child’s body, holding the toddler high and snug in a traditional British carry — a style seen throughout Wales, Ireland, and parts of England and Scotland. The baby’s arms are free, the weight evenly distributed, the wrap tied simply but firmly at the waist.

The fabric itself is thick and warm, likely pulled straight from daily use — not a purpose-made baby carrier, but a shawl, adapted without fuss. Its long fringe hangs over the mother’s skirt, adding both beauty and texture to this functional hold. Both mother and child wear their Sunday best — lace collars, neatly styled hair — suggesting this photo was taken on a special occasion, though the way the baby is carried is clearly second nature.

A mother stands on the steps of a weathered stone building, her baby wrapped close against her body in a soft, fringed shawl. The cloth is drawn high across her shoulder and tied low around her waist, creating a secure front carry in the familiar British style — simple, warm, and instinctive. The baby is held upright, nestled into the folds, dressed snugly in a bonnet and coat, with only the round cheeks peeking out.

She is not barefoot — her feet are planted firmly in shoes that speak of practicality, not performance. Next to her, another woman pauses in the doorway, bag in hand, mid-conversation or mid-laughter, the kind of easy exchange shared between neighbours or kin.

This is a glimpse of daily life: textured walls, worn steps, and the quiet strength of a mother who carries her child not just with fabric, but with presence. There’s nothing staged here — just care, community, and the enduring rhythm of holding babies close in the everyday.

A woman stands holding a young child wrapped snugly against her chest in a woolen shawl, in the traditional style seen in Britain and Ireland. The cloth crosses diagonally over one shoulder and under the opposite arm, cradling the child high and close, the fringe trailing neatly below her waist. The little one wears a knit hat and leans calmly into the embrace, their body supported in an upright, instinctive position.

Beside her stands a second woman, perhaps her daughter or daughter-in-law, and a group of children in coats and woollen caps — their eyes watchful, their stances serious. The backdrop is plain and unpolished — a timber fence, rooftops, and the quiet echo of hardship.

Two women stand outside a doorway, smiling in conversation with a third woman wrapped in a long overcoat. Each of the first two carries a baby in a woollen shawl — the cloth pulled securely over one shoulder and tied at the waist in a traditional hip or front carry. The babies are held upright, nestled close into their mothers' bodies, their weight supported entirely by the fabric.

One child sits alert on the hip, facing outward, while the other rests more quietly against the chest. Both shawls are checked wool, the kind long used for warmth and carrying — familiar, practical, and woven into daily life.

There is ease in their posture, closeness in their exchange. The babywearing is unremarkable in the best way — simply part of what’s worn, part of how the day is lived. These are children carried not as a task, but as a natural extension of the conversation, the doorstep, and the moment.

A group of women stands gathered at a doorway, caught in conversation and laughter. Their clothes are practical, skirts above the ankle, hair covered or waved into shape. One leans on a broom, another holds a folded shawl, and two stand barefoot on the stone threshold. The sense is one of rhythm and familiarity — neighbours pausing between tasks.

To the right, one woman carries a baby on her hip, wrapped in a length of cloth tied around her waist and over one shoulder. The baby is seated securely, upright and calm, wrapped in close to the body.

In Ireland and Scotland, large woolen plaids and shawls served a similar purpose, providing warmth and security in damp, cold climates. Babies were often wrapped close as mothers tended gardens, gathered peat, or carried water from the well. Gaelic songs and whispered stories accompanied these tasks, embedding language and cultural memory into each gentle sway.

Ireland

A rich visual archive of Irish babywearing traditions can be found through the work of A History of Irish Babywearing Their collection of historical photographs and stories showcases how Irish caregivers have long used shawls, blankets, and simple cloths to carry their children—whether working in fields, walking village roads, or tending to daily tasks. These images capture the quiet strength and resourcefulness of Irish families, reflecting a deep cultural heritage of keeping babies close, safe, and connected to their community.

Two women stand outside a church, framed by the Mass schedule and a Trócaire Lenten Campaign poster behind them. Both are wrapped in large woollen shawls, drawn across the body and over one shoulder in a way that signals both warmth and function. Each woman carries a baby, nestled into the folds — one almost completely hidden, the other more visibly supported beneath the check of the cloth. Their stance is relaxed, their presence grounded.

This image is rooted unmistakably in Ireland. The Mass times posted on the wall follow the familiar Catholic format seen across the country, listing morning and evening services for Sundays, Holy Days, and weekdays. The Trócaire poster beside them — showing another mother carrying her child in a shawl — further anchors the scene in Irish church life, where these campaign prints have long appeared during Lent.

The cobbled lane bustles with energy — traders calling, children gathering, bundles of goods laid out on makeshift tables. This is Coles Lane in Dublin, Ireland, captured in a rare colourised image from the early 20th century. The mist of a cool morning hangs low, softening the sharp corners of brick and cloth, but not the vibrancy of the street.

Along the right-hand edge, a woman carries her baby wrapped snugly in a dark shawl, cradled high on her front in the familiar style used by working-class mothers across Ireland and Britain. The baby’s head is swaddled, the body supported close, wrapped securely in fabric that blends seamlessly with the mother’s outerwear — practical, warm, and instinctive. Another mother nearby carries her child in the same way, barely distinguishable from the folds of her coat.

This haunting historical photograph shows an Irish tenant family during the eviction crises of the 19th century. The mother holds her young child wrapped tightly in a large shawl, a simple but powerful way to keep little ones warm and close amidst uncertainty. The family's worn clothing and solemn expressions reflect the deep hardship and resilience faced during this period. Shawls were commonly used by Irish women both for warmth and for carrying children, embodying practicality and motherly care in the harshest circumstances. This image powerfully illustrates how, even in moments of loss and displacement, the instinct to hold and protect children remains at the heart of family life.

In this historical photograph, an Irish mother stands proudly outside her stone cottage, carrying heavy milk pails and her baby at the same time. Her traditional dress and patterned headscarf speak to rural Irish life in the late 19th or early 20th century, a life of hard work and close family bonds.

The baby is snugly secured on her back using what appears to be a simple woollen shawl or large cloth — a style widely used in Ireland and across the British Isles. This improvisational carrying method shows the practical and resourceful spirit of mothers who needed to keep little ones close while tending to essential tasks.

Beside her stands her older child, barefoot and smiling shyly, embodying the warmth and resilience of rural Irish families. Together, they reflect the timeless story of mothers everywhere: weaving care and labour into one continuous rhythm, strengthened by love and community.

Scotland

In Scotland, the traditional plaid — a large woven tartan shawl — was not only a marker of clan identity but also a practical tool for daily life. Folded into a triangle and tied securely, the plaid became an improvised baby carrier, keeping little ones close while caregivers worked the land or moved through rugged highland paths. These carrying techniques were quietly shared from one generation to the next, reflecting the resourcefulness and deep textile traditions of Scottish families. In each wrap and knot, we find not just practicality but a living story of warmth, belonging, and ancestral connection.

A Scottish traveller family walks the roadside together, each step part of a shared story. At the front, a man plays the bagpipes as he walks, the music drifting across the quiet road, rooted in place and kin. Beside him, a young woman carries her baby high on her front, wrapped securely in what appears to be a traditional Scottish plaid — tied in the familiar British style seen across regions like Wales, where shawls and cloth wraps have long kept babies close to their mothers' hearts.

English and rural British families also used blankets or simple cloths to secure infants, particularly among working-class and farming communities. Carrying kept babies near the heartbeat and warmth of the caregiver, fostering quiet moments of connection amid hard labor. But the popularity of prams amongst the upper classes after Queen Victoria embraced the new invention had a flow-on effect. The rich would hand down unwanted perambulators to servants and tenants, the use of which gradually replaced the art of babywearing. By the mid-century, only pockets of traditional carrying remained.

A barefoot woman stands at the water’s edge, her baby wrapped snugly against her chest in a checked cloth, tied in the classic British style we recognise from Wales and parts of Scotland and northern England. The wrap crosses over her shoulder and around her waist, creating a secure and supportive pouch for the child, who peers out from the folds with a bonneted head and wide eyes.

England

Two women walk down a cobbled street, laughing as they carry bundles of firewood in their arms. One also carries a toddler — wrapped high and close across her chest in a woollen shawl, the child seated securely at her hip in the familiar British carrying style. The fabric is drawn over one shoulder and under the opposite arm, leaving her hands free to work. The child leans back slightly, calm and steady, folded into the rhythm of the day.

The scene is set in an early 20th-century industrial city — likely Manchester, Liverpool, or London — where narrow terraced housing lines the streets and children gather in the background. The women wear practical skirts and coats, their feet firmly planted in sturdy shoes as they move with purpose and ease.

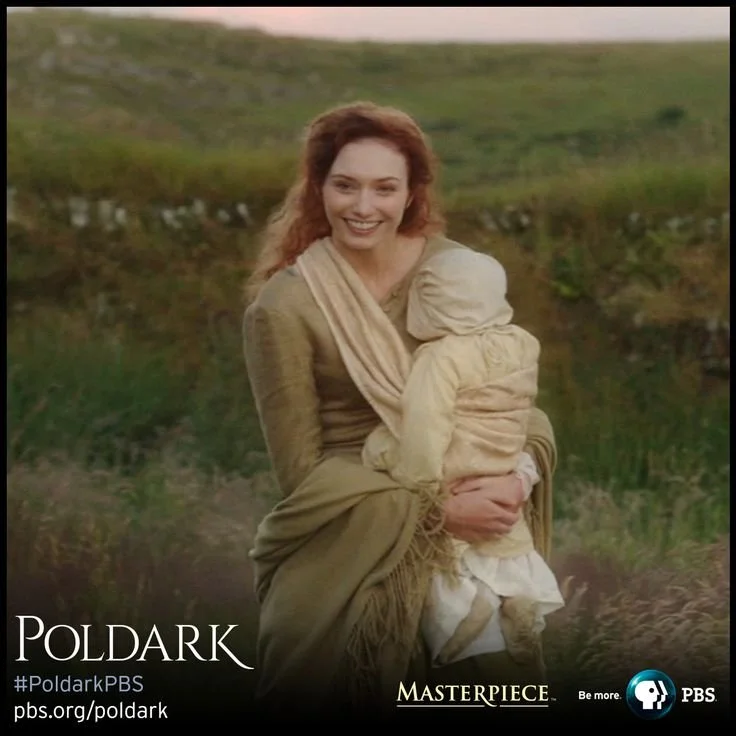

A modern glimpse into these older practices can be seen in the BBC adaptation of Poldark, where Demelza is depicted carrying her baby in a shawl tied like a sling. While dramatized, this portrayal is rooted in historical reality: in 18th-century rural Britain, working-class women often used shawls and simple cloths to keep their babies close while managing daily tasks. These improvised carriers were practical and comforting, reflecting a longstanding tradition of resourcefulness and embodied care. The series costume designers aimed for historical accuracy, subtly honoring the quiet, often overlooked labor of women — the same labor that shaped daily life and kept communities alive.

Colonization within the Isles — with English dominance over Welsh, Irish, and Scottish cultures — contributed to the suppression and loss of many traditional practices, including carrying methods. Industrialization and the promotion of prams further distanced families from these intimate, embodied ways of nurturing.

Fleeing sectarianism, Belfast refugees at the Kildare Street Club, 1922.

Today, a renewed interest in reclaiming British cultural heritage has led some families and educators to explore these old methods again, weaving ancestral connection into modern parenting.

To be carried in the British Isles is to be wrapped in mist and wool, held close in song and story, and carried forward in silent threads of resilience and belonging.

A note of gratitude and respect

We respectfully acknowledge and honor the individuals and communities depicted in historical images throughout this series. Many of these photographs were taken in times and contexts where informed consent as we understand it today was not sought or given, and some may have been created through coercion or exploitation.

We share these images with the deepest gratitude, not to romanticize or objectify, but to recognize and celebrate the strength, resilience, and wisdom of these cultural practices. We hold these ancestors and knowledge holders in our hearts and aim to represent their traditions with integrity, humility, and care.

We commit to continuing to learn, listen, and uplift the voices of contemporary community members and descendants, and we welcome guidance on the respectful sharing of these images.