Babywearing in the early 21st century: A Global Revival

Post-9/11 and early 2000s: Security and identity

The attacks of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent "war on terror" ushered in a global atmosphere of heightened security and individual caution. In parenting, this sometimes translated into hypervigilance and an increased emphasis on safety standards, while also renewing some families' desire for closeness and simplicity in turbulent times.

From Tradition to Trend: The Modern Resurgence

As the 21st century unfolded, babywearing education and community support blossomed worldwide. In Europe, babywearing schools such as Die Trageschule® Dresden and ClauWi® in Germany, and Slingababy in the UK, laid the foundation for modern consultant training. These schools emphasised optimal positioning, infant safety, cultural sensitivity, and biomechanics, creating a global network of highly skilled educators.

In Australia, small businesses and community leaders played a vital role in spreading babywearing knowledge. Notably, Tenoki, based in Melbourne, pioneered hands-on education and retail, helping countless families access quality carriers and learn safe techniques. Their influence was instrumental in shaping a culture of informed, supported babywearing across the country.

Brands such as Wrapture and Ankalia designed and manufactured woven wraps locally, showcasing Australian creativity and craftsmanship. These wraps gained loyal followings both domestically and internationally, highlighting Australia as a unique contributor to the global babywearing scene.

The Rise of Ergonomic Carriers and the M-Position

Meanwhile, Ergo, founded in 2003 by Karin Frost in Maui, offered a revolutionary alternative to narrow-based carriers like BabyBjörn. Its ergonomic design allowed babies to be carried into toddlerhood comfortably and soon became the go-to carrier from around 4–6 months of age. By 2010, Ergobaby had achieved $23 million in sales and was sold to Compass Diversified Holdings to expand globally. Germany’s Manduca followed a similar pathway, arriving in Australia shortly after Ergo and offering another ergonomic choice.

The T.I.C.K.S. guidelines for safe babywearing were developed in 2010 by a UK community initiative called Baby Sling Safety, led by Alexandra (Alex) Savva. Alex, a passionate babywearing advocate and founder of Joy and Joe Baby, worked with other UK carrying educators and sling librarians to address safety concerns, especially after incidents involving bag-style slings. While not developed by medical professionals, these guidelines drew on practical experience and existing medical knowledge around airway safety and infant positioning.

The M-position, often called the “spread-squat” or “frog” position, was promoted around the same time in Europe and the UK, highlighting the importance of healthy hip positioning to prevent hip dysplasia. Though widely supported by orthopedic recommendations, its advocacy was largely carried forward by babywearing consultants rather than clinical researchers.

Together, these community-driven guidelines and positions became foundational to modern babywearing practice, prioritising infant safety and comfort while remaining accessible and easy to share among parents.

For newborns, many Australian parents turned to the Hug-a-Bub, a stretchy wrap created in the early 2000s by childbirth educator Suzanne Shahar and designer Tania Palmer. Hug-a-Bub later added ring slings before going into liquidation in 2016 and was eventually taken over by Fertile Mind and later acquired by a global entity.

Woven wraps from Didymos and other European brands became more accessible through dedicated Australian small businesses, reducing high postage costs and opening up a world of beautiful, versatile carrying options. Ring slings, beloved by fans of Dr. William Sears (whose wife Martha coined the term “babywearing”), also gained popularity, alongside imported meh dais that competed with Australian Breastfeeding Association (ABA) products.

Global Financial Crisis (2008)

Economic instability led many families to re-examine values around consumption and security. Some parents turned toward minimalism, sustainability, and simplified lifestyles, which included a renewed interest in practices like babywearing and shared family sleeping arrangements.

In late 2009, Tula was founded in Poland by Ula and Mike Tuszewicki, initially with the modest goal of selling one carrier a day in Europe. After moving to San Diego in 2011 and connecting with local babywearing groups, they expanded into the U.S., and word quickly spread worldwide. By the twenty-teens, Tula had developed a cult-like following, with Australian parents paying high prices to buy online and a thriving pre-loved market emerging.

Social Media and the Babywearing Community

In the United States, groups like Babywearing International and local lending libraries flourished. New Zealand saw vibrant local groups like Babywearing Wellington and Babywearing Auckland, integrating babywearing into an active, outdoor lifestyle. Across Asia, traditional carrying methods like podaegi, bei bei, and onbuhimo continued alongside modern ergonomic options, maintaining cultural practices even as Western brands entered the market.

We had little idea where this was going to lead us!

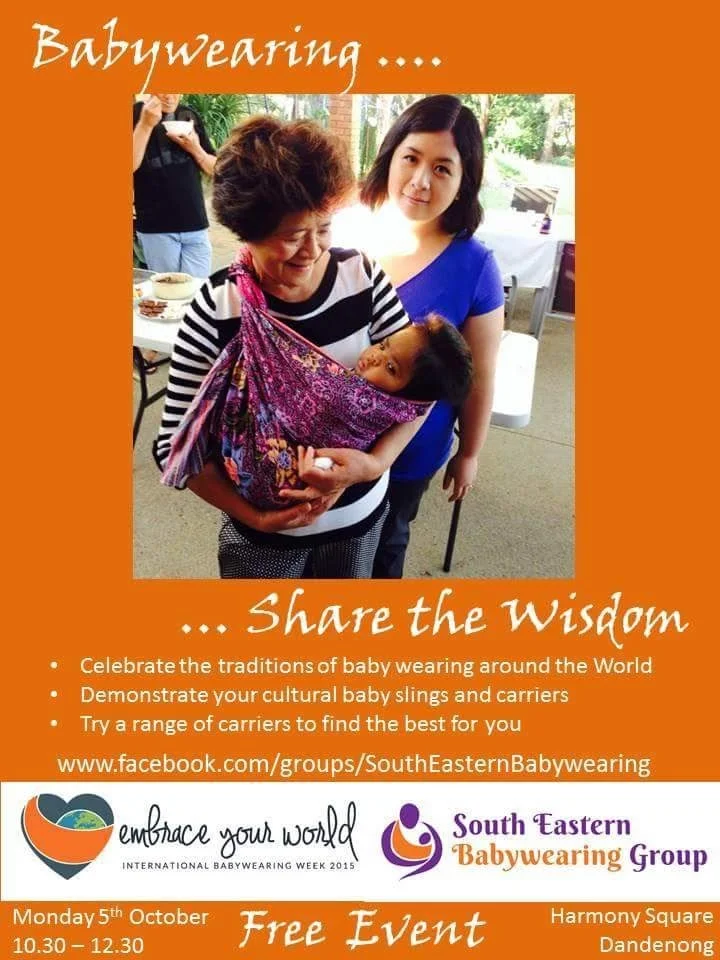

Babywearing groups and community meet-ups thrived, offering workshops, carrier try-ons, and peer support. The first Australian Babywearing Conference became a landmark event, bringing together educators, small businesses, and families to strengthen national connections.

Our group even participated in visual images competitions and won prizes to grow our demonstration library collections — memorable wins in 2015 and 2018, allowing us to offer more options and share hands-on experiences with families.

Another highlight each year was International Babywearing Week, celebrated enthusiastically before COVID-19. We hosted local events, community walks, themed days, and photo contests, creating joyful opportunities to raise awareness and bring parents together in a spirit of fun and solidarity.

2014 - Ikea, Springvale

2015 - Tesselar Tulip Farm, Silvan, Victoria

2016

The movement’s growth was fuelled further by passionate educators and advocates on social media. Names such as Anna Horn (NINO Babywearing), Jillian David (Babywearing International), Dr. Rosie Knowles (Carrying Matters in the UK), and Australia’s Brooke Maree became central figures. Educators used Facebook groups, Instagram stories, live videos, and YouTube tutorials to guide new parents, answer fit questions in real time, and normalise babywearing in diverse everyday settings. Their dedication over more than a decade shaped the online babywearing landscape and provided free, accessible education to families worldwide.

A unique evolution within this movement was the growth of Kangatraining, an Austrian concept founded by Nicole Pascher that blended babywearing with postnatal fitness classes. Kangatraining arrived in Australia and New Zealand in the early 2010s and quickly gained popularity. The program allowed caregivers to exercise safely while wearing their babies, focusing on pelvic floor recovery and core strength. Classes fostered community, encouraged gentle postpartum movement, and celebrated bonding through shared activity. By 2025, Kangatraining had become an integral part of the babywearing landscape, empowering many parents to embrace fitness and connection simultaneously

COVID-19 pandemic (2020 onwards)

The global pandemic reshaped family life dramatically. Lockdowns, remote work, and health anxieties led many parents to hold their children closer, both physically and emotionally. There was a surge in home-based care, homeschooling, and a new appreciation for ancestral practices that emphasise body contact and connection.As the decade ended, the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically reshaped the landscape. Babywearing groups, face-to-face workshops, and sling meets were suddenly halted. Many local consultants lost their primary way of connecting with families. Small businesses struggled under supply chain disruptions and lockdown restrictions, while multinational brands, with greater resources and online infrastructures, stepped in to fill the gap. This shift further consolidated market share for large companies and made it harder for local makers and small-scale educators to sustain their work.

In a moment that quietly captures the resilience of new parenthood during a global pandemic, Kaitlyn holds her sleeping baby close in a soft structured carrier. Both mother and child are nestled against one another — the baby deeply relaxed, Kaitlyn’s masked face revealing only her calm, steady eyes. The textured monochrome pattern of the carrier stands in contrast to the stark clinical setting behind them, where PPE bins and trays remind us of the heightened precautions of 2020. This image speaks to the quiet strength of mothers who carried on — literally and figuratively — through uncertainty, bringing comfort, safety, and connection to their children amid isolation and disruption.

Parents, isolated and often unable to access in-person support, turned to social media and online marketplaces. Instagram and TikTok became primary sources for quick tutorials and product recommendations. While this increased visibility, it also led to a dilution in the quality of education. Short, catchy videos often prioritised style over substance, leaving out critical information about safe positioning and biomechanics. YouTube became a go-to resource for longer tutorials, but without the personalised feedback once provided in local meets, many parents struggled with carrier adjustments and troubleshooting.

Challenges and Controversies in Modern Babywearing

The rising popularity of carriers designed to face babies away from the caregiver — often promoted by influencers and big brands — highlighted a shift toward consumer convenience and aesthetics over developmental needs. While forward-facing options can be used safely in moderation and at appropriate ages, the marketing emphasis on this feature sometimes overshadowed the importance of connection and inward-facing support.

The “crotch-dangling” design of narrow-based carriers was identified as a risk for babies pre-disposed to hip dysplasia, leading to awareness attempts and techniques like the “scarf hack”

Woven wrap usage, once nurtured by community groups and sling libraries, declined in many regions as fewer parents had opportunities to learn wrapping techniques in person. The tactile, social experience of borrowing wraps, sharing skill-building circles, and developing confidence through peer support has been difficult to replicate online.

In response, many babywearing consultants pivoted to virtual services: video consults, live group webinars, and online troubleshooting sessions became common offerings. While this increased access for some, it lacked the warmth and nuanced guidance of in-person mentorship. Additionally, parents today are often left to sift through a sea of content, piecing together guidance from influencers, brand pages, and community forums without always knowing which sources are evidence-based and truly supportive.

21st-century trends: Digital life and reconnection

Today, parenting unfolds in a hyper-digital world shaped by social media, global information exchange, and evolving cultural conversations around inclusivity and mental health. Babywearing has become both a practical tool and a statement of values: prioritising touch, responsiveness, and conscious living.

Parents now draw inspiration from global traditions, reclaiming the wisdom of ancestors while navigating modern challenges — a testament to the enduring human instinct to keep our babies close, safe, and loved.As of 2025, parents seeking babywearing information and products predominantly look online — to Instagram reels, TikTok clips, YouTube deep dives, and online reviews. While this digital landscape has broadened access, it has also created new challenges around misinformation and the loss of community-based wisdom. Many parents still long for local meets and in-person connections, underscoring the enduring value of community and shared learning.

Ultimately, despite the evolving market and digital trends, the heart of babywearing remains unchanged: keeping babies close, responding to their needs, and fostering deep bonds. In this complex new era, the challenge is to hold on to these core values, ensuring that parents everywhere feel supported, educated, and empowered to carry their babies safely and lovingly.